The early 1900s was a period of much experimentation with different home canning methods.

One of the more now hard-to-believe methods devised was called “fractional sterilization” or “intermittent processing.” (Outside the canning world, it was often known as “Tyndallization”, being named after the 19th century scientist John Tyndall who proposed the method.)

The process was designed to encourage bacteria to colonize your food. You boiled your food in daily each day for a short time for three days, and afterward let it to sit on the counter to fester each day in between.

The idea was that after each successive cooking, the warm environment in the jars would encourage bacteria to germinate from boil-resistant spores resident in the jar, only to be killed off the next day by the boiling because live bacteria are less hardy than spores against boiling. This would be repeated until all the spores had germinated and been killed off in their weaker bacteria state, and it was decided somehow that three boilings was the magic number that would do the trick.

To be clear, this is process that has been thoroughly discredited for nearly 100 years now, and probably caused many deaths. You should not attempt to can using this method. This article is a historical piece presented to provide cautionary background information in the event readers see someone on the Internet attempting to revive it as a “forgotten art.”

Here are some passages from canning books of the time to tell the story.

The process in detail

In 1914, a writer named Emily Riesenberg explained it like this:

Instead of cooking the vegetables only once, three cookings, on as many successive days, are advisable. The first cooking may kill only the bacteria, but not the spores, the offsprings of the parent bacteria. Though boiling will kill the mold and perhaps most of the bacteria, those that escape will again develop spores after the vegetables have cooled. Hence it is necessary to cook all vegetables a second time, and in most cases the third cooking is safest, as it will surely destroy any spores that have developed and are lying dormant. To realize the importance of this repeated cooking, you must remember that one bacteria will develop millions of spores in one day, and as spores contain the greatest amount of vitality, thorough boiling is necessary to insure good results…..Do the canning in a clean, well-swept room, wear clean cotton clothes, an apron preferably, and a neat mobcap over your hair.” [1] Riesenberg, Emily. Preserving and Canning. New York: Rand McNally & Company. 1914. Page 93 – 95.

Notice in the directions the clean cotton clothes, thrown in as a ‘Hail Mary’ measure, even, as if what you were wearing could influence the safety or quality of your home canned goods.

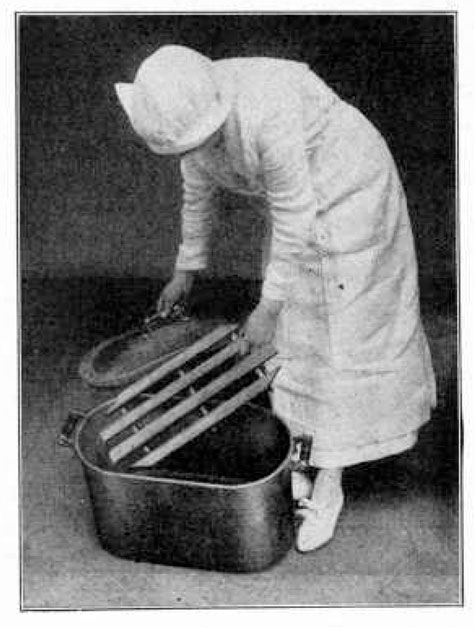

Photo source: Creswell, Mary E. and Ola Powell. Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables. USDA. Farmers’ Bulletin 853. July 1917; revised 1918. Page 10.

Louise Stanley, who would become one of the first USDA canning leaders, even advised the process in 1914:

Canning by Heating on Three Successive Days. By fractional sterilization we mean the cooking of the material to be canned for a shorter length of time than is necessary for complete sterilization, on three successive days. It is one of the ways in which we are able to kill those microorganisms which form spores (see page 5). The time necessary is usually about 1 hour on each of three successive days. The time depends upon the size of the can and the consistency of the material. It is one of the the safest ways to can those vegetables which ordinarily give trouble. While it is slightly more difficult than the method which involves only one cooking, it can be used in cases where the other has proven to be ineffective. The method of cooking three successive days may be applied to all types of green vegetables, such as peas, beans, etc., with slight differences in the preparation and the length of time of cooking….”This may seem a great deal of trouble, but will prove very simple when once tried. You simply lift the steamer from the stove, leaving the jars in it until the next day, when you put back on stove and proceed as directed.” [2]Stanley, Louise and May C. McDonald. The Preservation of Food in the Home. University of Missouri Bulletin, Vol 15, # 7, Extension Series 6. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri. 6 March 1914. Page 20 – 21.

Here’s an explanation of it from 1918, with the appeal to science.

The process of boiling upon successive days is always employed in scientific work and is the one I always use, except with such vegetables as beets, which are very easily sterilized. The boiling on the first day kills all the molds and practically all the bacteria, but does not kill the spores or seeds. As soon as the jar cools these seeds germinate and a fresh crop of bacteria begin to work upon the vegetables. The boiling upon the second day kills this crop of bacteria before they have had time to develop spores. Among scientists this is called fractional sterilization, and this principle constitutes the whole secret of canning. If the housewife will only bear this in mind she will be able, with a little ingenuity, to can any fruit or vegetable…” [3]Breazeale, J.F. Economy in the kitchen. New York: Frye Publishing Company. 1918. Page 44.

In 1918, it was implied that more diligent, energetic and conscientious canners would use the fractional method. Note as well the habit of the time of alluding to hearsay and experience — “some practical housekeepers” — rather than evidence-based research. This type of thinking is still seen today amongst Cowboy Canners.

Here is a passage from Everywomans Canning Book, 1918:

The Intermittent or Fractional Method of Canning. This great resistant power of spores in vegetables makes the Intermittent or Fractional Method of canning the method chosen by some experts, especially for peas, corn, Lima beans, and string beans, on which bacteria are most likely to be found. Some practical housekeepers, who have been most successful in their home canning, are inclined to look with disfavor on the intermittent process, because of the additional labor involved in processing the jars three successive days. This method, they feel, discourages rather than encourages much canning. It is, however, widely used in the South, and it is well for every woman interested in canning her garden surplus to know how to do the intermittent method, since some years the bacteria are particularly virulent, and spoilage after careful processing would indicate that the intermittent sterilization would be best for that particular kind of vegetable. The principle of the intermittent method of sterilization is that spores not killed after the first processing will be less resistant and will probably be killed after the second day’s processing, and that after the third day’s processing there is very little chance of their living to do harm to the product.

To process intermittently, partially seal the product in the usual way and process one hour. Remove jar from container, seal, and set aside for twenty-four hours. On the second day, lift the spring of the clamp and set the partially sealed jar back in the processing bath, and process again for one hour. Remove, seal, and set aside for another twenty-four hours. On the third day, repeat this process. The jar is then ready to seal and put away. Fruits are never subjected to the intermittent method. It is absolutely necessary to follow accurately the time given in the tables for processing, if success is to be assured. It is quite common to hear the amateur say, in reporting failures, that she processed the beans thirty minutes, just as long as she ever cooks them for the table, and they spoiled. Thirty minutes will cook tender beans and make them edible, but it takes three hours’ continuous cooking to kill the spores living in them, and to prepare them so they will keep all winter. Do not compare the time you would cook your product for the table with the length of time it needs processing. Follow your time table if you wish for success.” [4] Hughes, Mary B. Everywoman’s Canning Book. Boston, Massachusetts: Whitcomb and Barrows. 1918. Page 5 – 6.

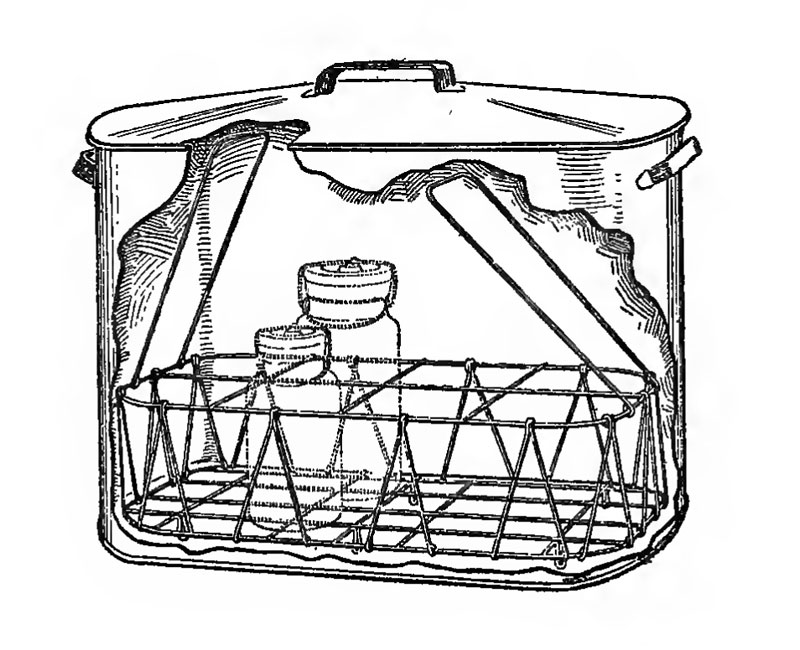

Lightning-style preserving jars were recommended as being particularly suited to intermittent processing:

For intermittent processing the lightning-seal jars are suitable, because the lifting of the wire clamp each day during processing insures that the jar will not be broken by expansion and the rubber not worn by the unscrewing of the cap.” [5] Creswell, Mary E. and Ola Powell. Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables. USDA. Farmers’ Bulletin 853. July 1917; revised 1918. Page 12.

The USDA was still advocating intermittent canning in 1918. Notice in the following passage, though, the imprecision: “rarely do any spores fail thus to develop”, and “will ordinarily sterilize….” They really just didn’t know for sure what was going on, and so couldn’t make the kind of solid guarantees that we would expect and demand today.

The spores of some species of bacteria have been known to resist even five hours’ boiling. Since this gives a chance for failure, the laboratory practice of intermittent or fractional sterilization is applied to household canning when a hot-water canner is used for processing certain vegetables. Intermittent sterilization consists of applying boiling temperature to vegetables already packed in containers for a period on each of three successive days, sealing the jar immediately after each boiling or “processing” if the lid has been loosened to allow for the expansion caused by heat. After each daily processing the containers are kept at ordinary temperature, under which the spores not killed by boiling develop into bacteria of the easily killed vegetative or growing stage, which are then destroyed by the next period of boiling. Rarely do any spores fail thus to develop and be destroyed by the third processing. Processing for 1 to 1 ½ hours in a water bath at boiling on the first day, repeated on the second and third days, will ordinarily sterilize beans, peas, and corn in quart jars, if these vegetables are selected properly and handled carefully. In very warm weather an interval of only 18 hours between first and second processings is advised. ” [6] Creswell, Mary E. and Ola Powell. Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables. Page 6.

Research confirms the process is dangerous, but is ignored at first

In 1919, a researcher, Georgina Spooner Burke, documented that botulism survived this fractional canning method:

In August, 1917, Mrs. M. of Berkeley, California, canned some string beans from her garden. She sterilized them by the fractional method. In January, 1918, it was found that four of the seven jars of beans contained B. botulinus. The contents of one jar were fed to some chickens and 24 of them died of botulism, “Limberneck.” [7] Burke, G.S. The Occurrence of B. botulinus in Nature. Jour. Bacteriol., 4, 541. 1919. Page 549.

Gerald Kuhn, who pioneered the modern USDA Complete Guide, noted that Burke’s research also showed that the “three separate days” theory didn’t hold water. Botulism spores often just delayed germinating until after the third day:

However, another early report by Burke (1919)…. showed a much greater heat resistance of the spores of C. botulinum. Her experiments with 10 strains of C. botulinum involved heating suspensions of free spores at various temperatures and pressures for different periods of time. Conclusions from her studies include….. Fractional sterilization on three successive days was of doubtful value because the initial exposure to 100 C for 15 to 60 minutes delayed the germination of the spores until after the third sterilization period.” [8] Andress, Elizabeth L and Gerald Kuhn. Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. II. Early History of USDA Home Canning Recommendations. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, Cooperative Extension Service. 1983.

It was noted in the Journal of Bacteriology:

Burke (1919) reported that while exposure to a temperature of 100 C. may not kill spores of B. botulinus their vitality is weakened so that germination is delayed. Spores of this organism survived 3 hours boiling at 100 C., and 5 hours boiling was considered insufficient to sterilize. Fractional sterilization, because of delayed germination, was held of doubtful value.” [9]Magoon, C.A. Studies upon Bacterial Spores. Thermal Resistance as Affected by Age and Environment. Journal of Bacteriology. v.11(4); Apr 1926. Page 281.

Last gasp in America, with a name change

By the 1920s, the term “intermittent” had for the most part won out over “fractional.”

The USDA was still presenting it as an option in 1921 in Farmers’ Bulletin 1471, and gave intermittent processing times for many vegetables. Note that all kinds of doubts and cautions are starting to enter in.

Heating the can or jar in a water bath (or household steamer for two, three, or more periods, with intervals between the periods of from 6 to 24 hours, depending on the climatic conditions and products canned. This is known as the fractional or intermittent or three-period process. The temperature of the water or of the steam is, of course, to be maintained at the boiling point of water…. The use of the intermittent or three-period or fractional process is based upon the theory that a short period in boiling water (say of 1 or 1J hours) should suffice to destroy all bacteria in the vegetative form. By cooling the vegetable mass rapidly to room temperature and allowing it to stand for 6 to 24 hours, opportunity is given for surviving spores to “sprout” or grow into the vegetative form; after which the second processing period will kill all of the young, tender cells which have just germinated from the spores. The third processing period is added in order to catch newly germinated cells from any spores which may have failed to germinate within the first intermission. Processing in this manner is often successfully used with vegetables which are difficult to can. There are at least two contingencies which may sometimes interfere with its successful operation, especially in the hands of inexperienced canners and when the old rule “one hour on each of three successive days” is too strictly adhered to. In the case of those vegetables which pack very solidly in the can, such as spinach or corn, the heat penetrates so slowly that it may take an hour and a half for the material in the center of a glass quart jar to reach the boiling temperature, especially if packed after cold dipping without reheating. Of course the contents of the sealed jar are .always cold at the beginning of the second and third heating periods (although the operator does not begin to count the processing period until the water bath reaches the boiling point). Consequently in such cases the bacteria present are not subjected to boiling temperature at all, since the center of the mass may never reach the boiling point if heat is applied for one hour only during each processing period. To meet this difficulty, instructions are often given to use only the smaller sizes of glass jars or tin cans for processing corn and some other vegetables in those situations where experience teaches that difficulties are to be anticipated. Also the length of each processing period is increased from 1 hour to 1 ½ hours in some instances. In some cases the vitality of some of the most resistant spores appears to remain practically unimpaired by the first heating process. In very warm weather such surviving spores may germinate so rapidly that the young bacteria formed from them are able to form a second crop of spores within 24 hours. In such case the second processing period has no greater chance of killing all organisms than had the first one; it has, indeed, much less chance. It is for this reason that the suggestion has been made to decrease the interval between processing periods from 24 hours to 12 or 18 hours. … In the case of intermittent processing, however, the jars are cold at the beginning of the second and third periods, and these jars should enter a water bath which is “scalding hot” (140° to 175° F.) but not boiling nor hot enough to crack the jars.” [10]Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables. USDA. Farmers’ Bulletin 1471, October 1921. Pages 11, 13, 14, 19.

1921 is the last time intermittent processing was mentioned in American publications. By then boiling water canning and pressure canning were the two methods being endorsed, for high acid and low acid respectively.

In 1926, a note on the topic by the researcher C.A. Magoon explains why: that it just was not reliable.

It has been the practice of bacteriologists for many years to sterilize certain kinds of culture media by what is known as the fractional sterilization method, which consists in heating the substance at 100°C. or less for a definite length of time on each of three successive days. With the development of home food canning the intermittent process of sterilization has come into wide use, particularly in the Southern States, and the experience of home canners, as well as of bacteriologists in the laboratory, has been that at times this method of treatment fails. An explanation for such failure is to be found in the spore cycle study which indicates that often too long an interval has been allowed to intervene between the first and second heat treatments; types of food destroying bacteria which have short spore cycles find time to return to the spore form again, and thus survive the second, and sometimes the third cooking.” [11]Magoon, C.A. Studies upon Bacterial Spores. Thermal Resistance as Affected by Age and Environment. Journal of Bacteriology. v.11(4); Apr 1926. Page 260.

In Canada

Intermittent processing was still being presented as an option in Canada after it was disappeared in the States. It’s uncertain why, as Canada tended to follow US research and USDA recommendations closely (for better or worse, at the time.)

Agriculture Canada described the process in a 1928 home canning manual, though the department interestingly noted that it was more fuel-use intensive than other methods, something other previous writers had neglected to mention or didn’t think was important.

The fractional or intermittent method, which involves the carrying on of the sterilization period for three successive days, is used in the case of vegetables which are not strictly fresh, and is especially applicable and desirable for those vegetables lacking acid, such as peas, corn and beans. It is more thorough as regards sterilization than the one-day process owing to the fact that spores, which may develop after the earlier sterilization, are bound to succumb during the successive periods of sterilization, but the intermittent sterilization involves considerably more handling than is necessary in the one-day method; also more fuel is consumed.” [12]Hamilton, Ethel W. and W.T. Macoun. Preserving Fruits and Vegetables in the Home. Ottawa, Canada: Dominion of Canada Department of Agriculture. Bulletin 77. 1928. Page 7.

Intermittent processing resurfaced in a World War Two home canning bulletin in Canada from the Department of Agriculture. It’s difficult to imagine, why in a time of rationing a more fuel-intense method would be suggested, but then no one’s ever accused one government department of talking to the other.

Intermittent Sterilization – This method of sterilization is necessary when peas or beans are processed in a water bath. The product is sterilized one hour on each of three successive days. The jars may be removed from the boiler, the tops tightened and allowed to cool after each sterilization, or they may be allowed to remain in the boiler. It is not necessary to complete the seal if jars are kept submerged in the water between sterilization periods.” [13]Elliot, Edith L. Canning fruits and vegetables. Ottawa: Agriculture Canada. May 1942. Page 6.

Today

This sterilization method is sometimes used today to sterilize items such as seeds, which wouldn’t survive high heat sterilization methods and still be viable. A handful of home mushroom growers try to use it to sterilize the substrate that they want to grow mushrooms in.

Wikipedia says,

Tyndallization (aka “fractional sterilization”) is a process dating from the nineteenth century for sterilizing substances, usually food, named after its inventor, scientist John Tyndall. It is still occasionally used. The Tyndallization process is usually effective in practice. But it is not considered totally reliable—some spores may survive and later germinate and multiply. It is not often used today, but is used for sterilizing some things that cannot withstand pressurized heating, such as plant seeds.” [14]Accessed October 2016 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyndallization

Many home mushroom growers report, however, that the process doesn’t work reliably for them, resulting in failed crops as the mushroom spores are out-competed by other spores that survived the process. [15]https://www.shroomery.org/forums/showflat.php/Number/10145423. Accessed October 2016

Segen’s Medical Dictionary lists the process as “obsolete”: “An obsolete type of sterilisation described by J Tyndall (1820–1893) in which spore-forming bacteria in various stages of the cell cycle were destroyed by intermittent (e.g., one hour per day) steam sterilisation.” [16]fractional sterilization. (n.d.) Segen’s Medical Dictionary. (2011). Retrieved October 7 2016 from https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/fractional+sterilization

Summary

Using this sterilization for non-food items such as seeds, which are going to go into the ground anyway and knowing that you are going to have a failure rate that is acceptable, is one thing; using it for something that you are going to put into your mouth is something else entirely. For that, you want something 190% reliable, not something known to not be even 100% effective.

That aside, it was more work, and, more costly in cooking fuel. No tested times were ever arrived at; it was all guesswork. What tests were done showed that, when applied to home canning, the process was ineffective, and many times led to botulism toxin developing in people’s jars even after all that hard, repeated work.

It’s difficult to imagine that today’s consumer would tolerate the idea of partially processed food sitting out, unrefrigerated, in jars on counters deliberately hoping for germs to develop in it.

So if you see this around being suggested for home canning, run, don’t walk, away from that advice. It’s not anything new; it’s old as the hills and thoroughly discredited. Unlike other legacy food safety techniques which still work, such as Pasteurization named after Louis Pasteur, poor John Tyndall’s Tyndallization was a flop.

References