Home canning professionals in labs often need to measure how strong a vacuum is inside a sealed jar of home-canned food.

The vacuum matters, because it is what maintains the air-tight (“hermetic”) seal that resulted from processing the jar. A jar of home-canned goods for shelf-stable storage relies on that air-tight seal to maintain the sterilization levels that were achieved during processing.

Weak vacuums can often fail over time, causing the loss of the stored food and very vocal complaints from people who relied on canning advice from the pros.

Consequently, they measure the strength of a vacuum when advising:

- how much headspace to leave for a particular recipe;

- what types of jars and closure system they are willing to support.

NOTE: This is an advanced topic, only for the curious canner. You don’t need to know any of this otherwise!

Vacuum is measured in inches of mercury

Units of measure that you see for measuring vacuum, in the United States at least, are likely to be in inches of mercury.

The short form for the unit that you will see on gauges is inHg or just Hg.

You don’t necessarily need to know how that measurement was defined but if you are curious, here’s the background:

“Vacuum is generally expressed in ‘inches of mercury’…. Atmospheric pressure, at sea level, is sufficient to support a column of mercury thirty inches high, having a cross section of one square inch. If the air remaining in the ‘partial vacuum’ supports a column of mercury to a height of twenty inches, then the difference between the height of the two columns, ten inches, represents the ‘vacuum.'” [1]Maclinn, Walter Arnold. Some internal physical conditions in glass containers of food during thermal treatment. Master thesis. University of Massachusetts. 1935. Page 2.

Two general methods of measuring a vacuum’s strength inside jars

There are at least two ways of measuring the strength of a vacuum achieved inside a jar. One is a “destructive method” which involves piercing the lid. The second is via “non-destructive” methods which do not require piercing the lid.

Destructive method: piercing the lid

Piercing the lid is perhaps the simplest way.

A round metal gauge (that looks like a gauge you’d see on top a pressure canner, except with different measurements on it) is used. At its bottom is a steel needle which is used to pierce the metal lid of a jar (or tin.) A rubber gasket put around the steel needle helps to maintain an airtight seal while you are taking the measurement.

Here’s a public domain photo from the National Center for Home Food Preservation showing a gauge in action.

Credit: National Center for Home Food Preservation

Here is a pierce-type gauge, as sold by Fillmore Container (link valid as of January 2017.)

Non-destructive methods

While the “piercing the lid” method works great for metal lids, it obviously would shatter any glass lids immediately destroying a seal before its strength had a chance to be measured.

There are two other methods, classed as “non-destructive”, which can be used for both metal and glass lids.

(To be clear: no use of glass lids is currently recommended by the USDA for shelf-stable home canning. But, they are often used commercially. For instance, many “fancy” gourmet food products are commercially canned in Le Parfait’s glass lid jars, or Weck jars, and all aspects of that commercial canning including vacuum have to be thoroughly tested industrially by certified experts. This is how it can be done, for those who are curious about how they do it.)

Vacuum method

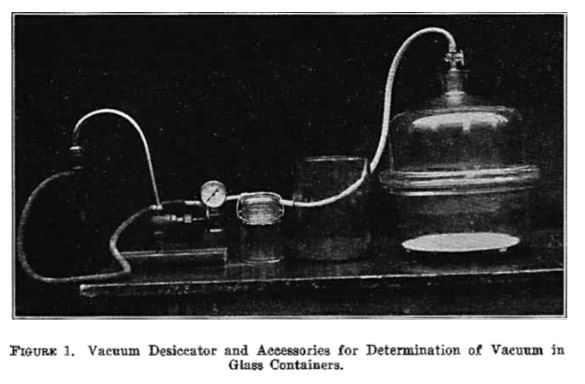

The sealed jar (or container) being tested is either (a) submerged in a container of water just big enough to hold it, OR (b) the seams of the edges can be coated with something such as a detergent. [2]”A vacuum box and a compressor create a high or low pressure vacuum while a detergent solution is applied to the test area. The detergent bubbles makes leaks visible within the created pressure envelope.” Vacuum Box Testing. Iris NDT. Access January 2017 at https://www.irisndt.com/us/specialized-ndt/vacuum-box-testing. This is then placed in a large glass bubble (usually known as a Bell jar), and sealed in. The bubble is then hooked up to an aspirator, which draws air out of the bubble. An attached gauge measures the changing vacuum inside the jar as the air is sucked out.

At a certain point, the vacuum in the bubble will become less than inside the jar, and the seal will naturally release itself when the vacuum is the same inside and outside the jar.

Evidence of this will be bubbles escaping through the water or the detergent coating. The reading on the gauge at this point for the vacuum is the vacuum inside the jar.

Img source: Maclinn, W.A. and C.R. Fellers. Vacuum determination in all-glass canning jars. Journal of Food Science, 1: 41–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1936.tb17768.x. 1936. Page 1.

A desiccator is connected with vacuum tubing to a water pump. The connections are tight so that a vacuum of 27 or 28 inches can be obtained. After loosening the bail, the jar is immersed in a large glass jar of water. Both jar and container are then placed in the desiccator and the aspirator allowed to slowly exhaust the air from the system. When the vacuum inside the desiccator becomes higher than that in the jar of food, the glass cover will lift, breaking the vacuum and allowing bubbles to escape from the jar. The vacuum gauge, which is set in the system between the faucet and the desiccator, is read at this time. The vacuum reading thus obtained shows that the vacuum present in the jar of food was slightly lower than the figure obtained. The slight resistance of adhesion between rubber rings and Jar is negligible in most oases of freshly sealed jars. In this work most jars were examined within a day after canning. …. In jars which have been sealed a long time, and where the rubber ring adheres tightly to the top of the jar and lid, the M. S. C. method gives greater vacuums than actually exist. This is because of the necessity of overcoming this sticking of the rubber ring to the glass. However, in most cases, even in old packs, the method gives quite satisfactory results on the whole, though it may be of no value on occasional jars.” [3]Maclinn, Walter Arnold. Some internal physical conditions… Pages 4, 6.

Weight method

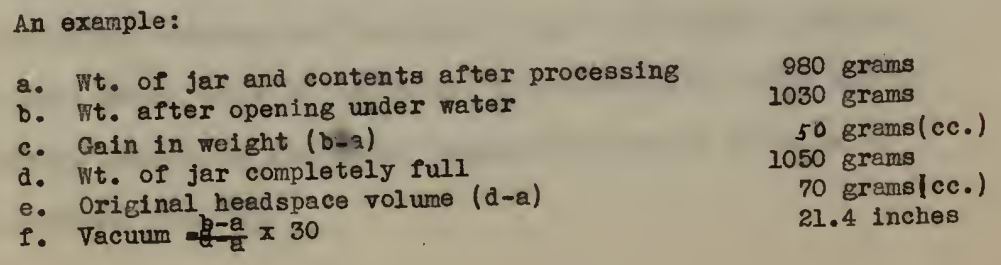

This is a bit more complex to explain, so we’re just going to quote from our 1935 researcher, Walter Maclinn.

The second method eliminates the error of adhesion between rubber ring and cover. The jar is weighed after processing. This weight included the complete container and contents. The jar is then immersed in water in an inverted position and the seal broken, permitting the headspace to fill with water in proportion to the vacuum in the headspace. Still holding the jar inverted, the water levels inside and outside the jar are made the same, the cap is replaced, the clamp tightened down, and the jar is then removed from the water, wiped off and reweighed. The difference in weight between the second and first weighing gives the amount of water which was sucked in. The lid is then removed and the jar filled completely with water, including the space under the glass cover. This weight minus the first weight gives the volume of headspace, and from the weight of water sucked in, the vacuum can be determined.” [4]Maclinn, Walter Arnold. Some internal physical conditions… Page 5.

Img source: Maclinn, Walter Arnold. Some internal physical conditions in glass containers of food during thermal treatment. Master thesis. University of Massachusetts. 1935. Page 5.

Summary

The destructive method is a quick and easy way to measure vacuum in a tin can, or in a Mason jar sealed with a metal lid, or a Tattler lid likely.

For glass lids, a non-destructive method is what would be required.

So, when you a statement such as this from the University of Wyoming —

….Jars requiring a glass lid, wire bail, and jar rubber have not been recommended since 1989 because there is no definitive way to determine if a vacuum seal is formed.” [5] Griffith, Patti. The time is ripe for summer melons. University of Wyoming Cooperative Extension Service. From series “Canner’s Corner: Enjoying Summer’s Bounty.” Issue Two. MP-119-2. Accessed March 2015

— it appears that that isn’t entirely accurate.

Such glass lid closure systems may not currently be supported for a host of other reasons: for instance possibly weak vacuums, failure rates, etc. To be intellectually thorough, however, one has to say that lack of a way to measure a vacuum seal would not be one of them, it appears. There has been a way to lab test for decades. (And of course, some people would say that at home with jars such as Weck there is always the “lift by the rim” test.)

That being said, none of this is applicable to home canners directly. It’s just background knowledge. By following tested recipes from reputable sources, with recommended closure systems, you should always achieve the required vacuum (unless something such as food on the rim, etc, interferes with the seal in the first place.)

References