A water seal was a stove-top “pot” designed to water bath process jars of food at temperatures slightly above boiling by means of slight pressure. It sold for home canning use at in the first few decades of the 1900s.

It is unclear exactly how the term “water seal” (or “water-seal”) came to be.

The devices appear to the modern eye to be a steam-punk curiosity from the Edwardian era.

This topic is for historical interest only and no preserving by this method should ever be attempted.

What exactly was a water seal canner?

A water seal canner was a device designed to trap steam and slightly raise the pressure inside, thereby also slightly raising the temperature.

Possibly the first description of a water seal canner in official canning publications is in a 1914 University of Missouri publication by Louise Stanley titled “The Preservation of Food in the Home.”

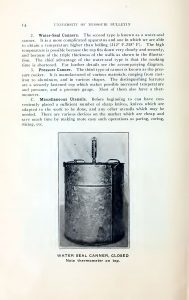

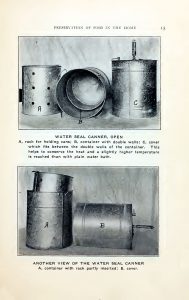

Water-Seal Canners. The second type [of canner] is known as a water-seal canner. It is a more complicated apparatus and one in which we are able to obtain a temperature higher than boiling (212° F – 218° F). The high temperature is possible because the top fits down very closely and securely, and because of the triple thickness of the walls as shown in the illustration. The chief advantage of the water-seal type is that the cooking time is shortened. For further details see the accompanying diagram.” [Ed: Diagram shown on two pages below.] [1]Stanley, Louise and May C. McDonald. The Preservation of Food in the Home. University of Missouri Bulletin. Extension Series 6. Vol. 15, No. 7. 6 March 1914. Page 14.

In 1917, Farmers’ Bulletin 839, authored by O.H. Benson, explained how water seals worked:

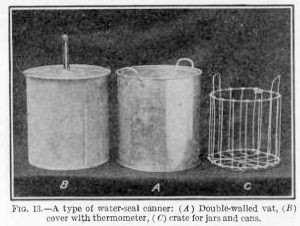

Water-seal outfits (fig. 13 [Ed: shown below]) consist of a double-walled bath (a) and cover (b) which projects down into the water between the outer and inner walls, thus making three tin or galvanized metal walls and two water jackets between the sterilizing vat and outer surface of the canner. A higher temperature may be maintained more uniformly with such an outfit than with the hot-water-bath outfits, since the free escape of steam is prevented and a slight steam pressure is maintained. The water-seal outfit may prove more economical of heat, especially in the canning of vegetables and meats, where high temperatures are necessary for complete sterilization.” [2]Benson, O.H. Home Canning by the One-Period Cold-Pack Method. Washington, DC: USDA. Farmers’ Bulletin 839. June 1917. Page 7.

To be clear, a water seal outfit was not a steam canner. You still fully filled it with water and immersed the jars in that water. The purpose of the trapped steam was essentially to raise the temperature of the water in which the jars were being water-bathed to a temperature above 100 C / 212 F.

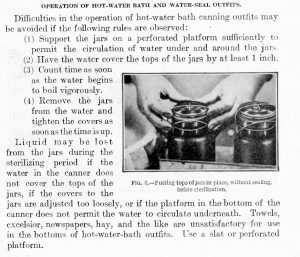

Use of boiling-water baths and water-seal outfits required the following rules: support of the jars on a perforated platform, covering the tops of jars with water by at least 1 inch, counting the time as the water began to boil vigorously, and removal of the jars from the water when the processing time was completed. While the need for immersion in water was recognized, the reason given for immersion was so that liquid would not be lost from jars during the sterilization period.” [3] Andress, Elizabeth L and Gerald Kuhn. Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. IV. Equipment and its Management – History and Current Issues. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, Cooperative Extension Service. 1983.

Adaptation into the marketplace

There were at least two brand names of water seal canners on the market, Duncan, and Cano.

The US government gave some water seal canners out for people to use in demonstrations in 1915:

The Mothers Club of the Sharon community will meet this afternoon at 2 o’clock in the Sharon church on the Mt. Pulaski road and Mrs David B. Parr and Mrs A.A. Hill will demonstrate canning….. Mrs David B. Parr, who started the work in this county, has received two canning outfits from O.H. Benson of the United States government at Washington, D.C. One is a steam pressure and the other is the hot water seal outfit. They are both splendid outfits and Mrs Parr will use them in her demonstrating.” [ref]Sharon Mothers to Organize Club. Decatur, Illinois: Decatur Daily Review. 17 March 1915. Page 7.

In 1918, a Florida-made model called “Cano” was advertised in Laurel, Mississippi.

A well-known writer at the time on home food preservation, William Cruess, wrote in 1918:

Several forms of steam pressure sterilizers for home use are on the market. There is one known as the “water seal outfit,” which gives temperatures only slightly above the boiling point of water. This is considered favorably by many home canners; because it requires only a small amount of water, is easily heated, and is inexpensive.” [4] Cruess, William V. Home and Farm Food Preservation. New York: MacMillan Company. 1918. Page 51

In June 1920, in Portsmouth, Ohio, Marting’s Store advertised water seal outfits for 12 dollars. (Pressure canners were $23.30) [5] Portsmouth Daily Times. Portsmouth, Ohio. 17 June 1920. Page 5.

In the same month, in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Wolf & Dessatier Department store advertised the Duncan Brand Water Seal canner for $12.00. [6] Ad in: Fort Wayne News And Sentinel. Fort Wayne, Indiana. 23 June 1920. Page 8. [Ed: possibly made by Arthur L. Duncan who filed many canning-related accessories patents in the 1920s ]

A maker of one model appears to have been a William Mueller of Texas, according to his obituary:

William Mueller, 66, who is credited with having brought the first gasoline powered engine to Fredericksburg and Billespie Country in 1902, died Tuesday, Dec. 26th, at 12:25 in a local hospital… Mueller was born on Sept. 13, 1837 in Shulenberg, Texas…. During his time in Fredericksburg and for the duration of ten years he was engaged in the hardware business at the present location of Joseph Bros, Garab, with Louis Kott. It was during these ten years in Fredericksburg that he brought the first gasoline engines to the county… during these years he also invented and patented a windmill oiler and a water seal canner, both of which were widely used.” [7]Obituary in Fredericksburg Standard. Fredericksburg, Texas. 28 December 1939. Page 8.

Advice on using a water seal canner

Iin general, sterilization times were given as requiring 10 to 20% fewer minutes than for water-bath canning

Advice for using a water seal canner was being given in the press as early as 1914:

Process the corn… 1 ½ hours in the water-seal outfits…” [8]Recipes for Canning Corn both Off and on the Cob. Joplin, Missouri. Joplin News Herald. 13 July 1914. Page 9.

In 1915, people were advised that a water seal canner could be used to pasteurize apple cider, to prevent its fermenting into alcohol:

Keeping Apple Cider Sweet – Fill fruit jars with fresh apple cider. Add tablespoonful of sugar to each quart. Place rubber and cap in position, partly tighten or cap and tip tin cans. Sterilize… in water seal outfit for 8 minutes… Note – if you desire the cider tart or slightly fermented let it stand two or three days before you sterilize, then add about two minutes’ time to each schedule given in recipe.” [9] How Canning is Done Now. Rapid City, Manitoba: Rapid City Reporter. 7 October 1915. Page 1.

In 1917, the USDA published the following official advice on operating a water seal outfit:

CLICK TO ENLARGE: Benson, O.H. Home Canning by the One-Period Cold-Pack Method. Washington, DC: USDA. Farmers’ Bulletin 839. June 1917. Page 8.

One unnamed column writer in Boston in 1918 told people when to start counting processing time:

“With the water seal outfit begin counting time when the thermometer reaches 214 Fahr.” [10]$10,000 Offered for Best Canning Work. Boston, Massachusetts. 4 August 1918. Women’s Section, Page 1.

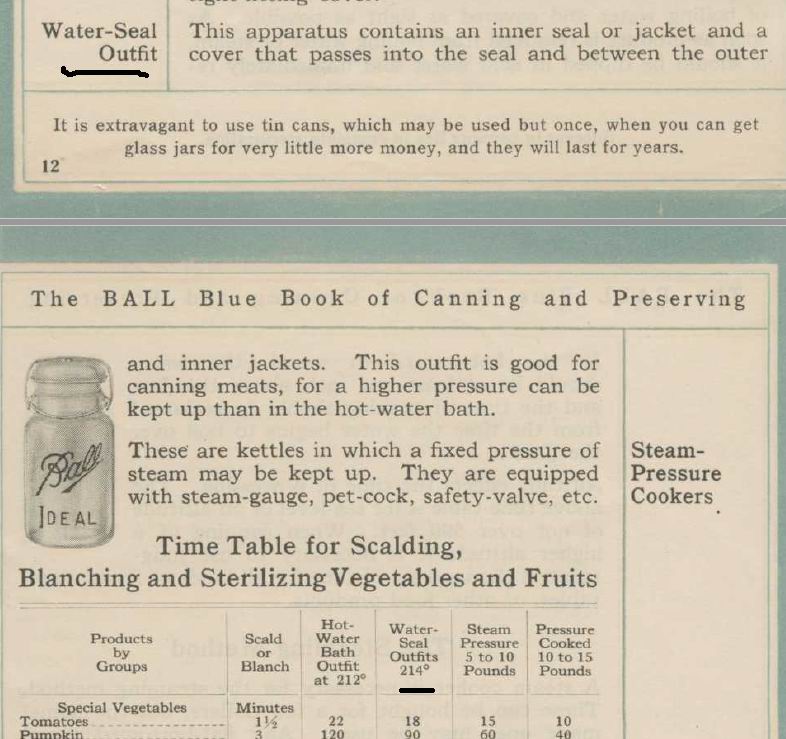

Ball gave processing times for some items in water seal outfits in the 1920s, in editions K and L of the Ball Blue Book.

WATER-SEAL OUTFIT. This apparatus contains an inner seal or jacket and a cover that passes into the seal and between the outer and inner jackets. This outfit is good for canning meats, for a higher pressure can be kept up than in the hot-water bath.” [11]Blue Book, edition K. Page 12.

Blue Book, edition K. Page 12. No processing times shown should be followed for anything.

The USDA dropped support for water seal outfits in May 1926, when they disappeared from that year’s update to “Canning Fruits and Vegetables at Home” (Farmers’ Bulletin No. 1471) by Louise Stanley, and never returned.

As for Ball, we don’t have access to edition M or N of the Blue Book to see if water seals persisted in those editions, but we do have access to the Blue Book O Edition, 1930, and by then, water seal canners had been dropped from the Blue Book, never again to reappear.

A modern similar technique would be steam canning, which is treated as an equivalent to water bath canning in terms of processing time. It differs from water seal outfit canning in that the jars are not immersed in water, and there is no allowance for any slight pressure that might result in a slightly higher processing temperature.

Another modern similar technique would be pressure canning. It differs from water seal outfit canning in that, again, the jars are not immersed in water, the canning device is fully vented of all air, and far, far higher pressure and resultant temperatures are achieved.

Antique curiosity now

It’s unclear how many of these water seal outfits have survived the hundred years or so since they were last made.

If you see one at flea market, now you’ll know what it is.

If it’s a good price, by all means get it if you wish to convert into a lamp or use as a decorative piece.

Don’t use it for home canning purposes, though. Any of the times ever given for it were just untested guesses, as is evident by seeing a few meat-product processing times for it. If you really want to be energy efficient for canning your high-acid products, get yourself a modern steam canner would which come up to processing temperature far faster anyway.

References