Water bath canning (sometimes called “Hot Water Canning”) is one of two methods of home canning (the other is pressure canning.)

It involves completely submersing sealed containers (usually jars) in a large pot of boiling water and boiling the jars for a specified period of time determined by (a) the type of food product inside the jars, and (b) the size of the jars.

The temperature inside the jars will never exceed 100 C (212 F) because it can’t; that’s the maximum temperature that the boiling water around the jars can reach.

Note: this page is for when you want to learn about the theory and reasons behind water bath canning. See here if you just need the bare actual how-to steps of water bath canning.

- 1 Steam canning replaces water-bath canning

-

2

The reason why water-bathing is done

- 2.1 1. Kills off many nasties that may be in the food product

- 2.2 2. Drives out air in the food and in the jar that could cause spoilage

- 2.3 3. As a fortuitous “by-product”, the driven-out air leaves behind a vacuum when the jar cools, sealing the jar

- 2.4 4. Ensure good, long-lasting shelf quality

- 2.5 5. Drive added acid such as vinegar into low-acid components

- 2.6 6. Good, safe procedure

- 3 What home canning products is water bathing used for?

- 4 Water bath canning cannot replace pressure canning. Ever.

- 5 The water bathing pot

- 6 You need some “padding” in the bottom of the pot when water bath canning

- 7 Water bath in a covered pot

- 8 Jar Sizes

- 9 When to sterilize jars before water bath canning

- 10 Jar Temperature

- 11 Double-decking for water-bath canning

- 12 Water levels for water bath canning

- 13 What about not completely covering the jars in water? i.e. “Low-water level canning”

- 14 Water bath times

- 15 Altitude increases time required for water bath

- 16 Minimum canner load for water bath canning

- 17 Rest your jars in the canner after water bath processing

- 18 Removing the jars

- 19 Discredited variants of water-bathing

- 20 Online Learning

- 21 Further reading

Steam canning replaces water-bath canning

In the summer of 2015, steam canning was approved by the National Center for Home Food Preservation as an equivalent process for water bath canning.

Steam canning saves money, energy costs, water, and reduces your carbon foot print. For this reason, Healthy Canning is recommending for beginning canners:

- Absolutely familiarize yourself with all the theory behind water bath canning because all of the food safety principles still apply;

- Instead of doing water bathing, however, start off right from the start practising steam canning instead.

The reason why water-bathing is done

The rationale behind water bathing addresses several factors:

1. Kills off many nasties that may be in the food product

The nasties can include “Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes and other pathogenic bacteria that might be present in the product.” [1] Bredit, Frederick, et al. Use of Linear Models for Thermal Processing of Acidified Foods. In: Food Protection Trends, Vol. 30, No. 5, 2010. Pages 268–272. Accessed March 2015.

“While these pathogens do not grow in acidified vegetables, they may survive long enough to cause disease. The infectious dose for E. coli O157:H7 may be as low as one to ten cells. For this reason, acidified vegetables must be processed to assure a five log reduction in acid resistant pathogenic bacteria….E. coli O157:H7 has been found to be the most acid resistant pathogen of concern for these products….The research done here documents how innocuous items such as pickled onions could hold E. coli that aren’t immediately killed by the vinegar, and what must be done to ensure its destruction.” [2] Bredit, Frederick, et al. Use of Linear Models for Thermal Processing of Acidified Foods. In: Food Protection Trends, Vol. 30, No. 5, 2010. Pages 268–272. Accessed March 2015.

“…the temperature achieved will kill off many yeasts, molds and bacteria..” [3] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. Accessed January 2015.

The process also depends on acidity (natural and / or added) in the food product to inhibit any microorganisms that survived the heat from being able to function. [4] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 42:00. Accessed January 2015 [Note: in a few very rare instances, reduced water activity in the food product may be relied on instead. ]

2. Drives out air in the food and in the jar that could cause spoilage

Oxygen causes food to degrade in appearance, flavour and nutrition. There’s not only air in the headspace of the jar, but there’s air inside the pieces of food you are canning, and minute air bubbles trapped in between each piece of food.

We want to drive all this air out of the storage container to avoid spoilage and ensure a long, quality shelf life for the food product being stored.

3. As a fortuitous “by-product”, the driven-out air leaves behind a vacuum when the jar cools, sealing the jar

“We do recommend a short boiling water process for even our truly gellied products and that is intended to get you the best quality in storage by getting that oxygen out of the headspace and getting a good vacuum seal. You have a much higher success rate of getting a vacuum seal with a short boiling water process than simply putting the lid on the jar and letting it sit, or even turning it over for a little bit and letting it then sit upright, you just, this exhaustion of air out of the headspace gives you a better chance at successful sealing.” [5] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 1:19:28. Accessed January 2015.

The seal prevents air (or any nasties) from re-entering the jar.

The seal that you get is technically known as a “hermetic seal.”

4. Ensure good, long-lasting shelf quality

“Our process time here is also meant to destroy any organisms like mould that might have gotten into the product as you filled the jar, and also to inactivate enzymes in the cucumber or other vegetable texture that might affect colour, flavour and texture in storage. Many pickle products are actually raw packs, where you might just put a raw green bean or raw slices of cucumber in a jar and then pour a hot brine over there and that may not be enough heat to inactivate enzymes for long storage periods and the boiling water process would take care of that for you.” [6] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 1:20:30. Accessed January 2015.

5. Drive added acid such as vinegar into low-acid components

When you are preserving pickles, you want the acid you are adding (usually vinegar) to permeate thoroughly all of the low-acid ingredients to ensure that they will be safe. Barb Ingham, Extension Agent at the University of Wisconsin, notes: “Heat processing will drive the acid into your food product” [Ed: she’s referring to the insides of the solids in your preserves, as in, inside the cucumber pieces, etc.] [7] Ingham, Barb. Purchasing and Using a pH meter. University of Wisconsin Extension Services. October 2009. Accessed March 2015.

6. Good, safe procedure

Water bath processing is an efficient process that is also very safe for the operator doing the processing at the time.

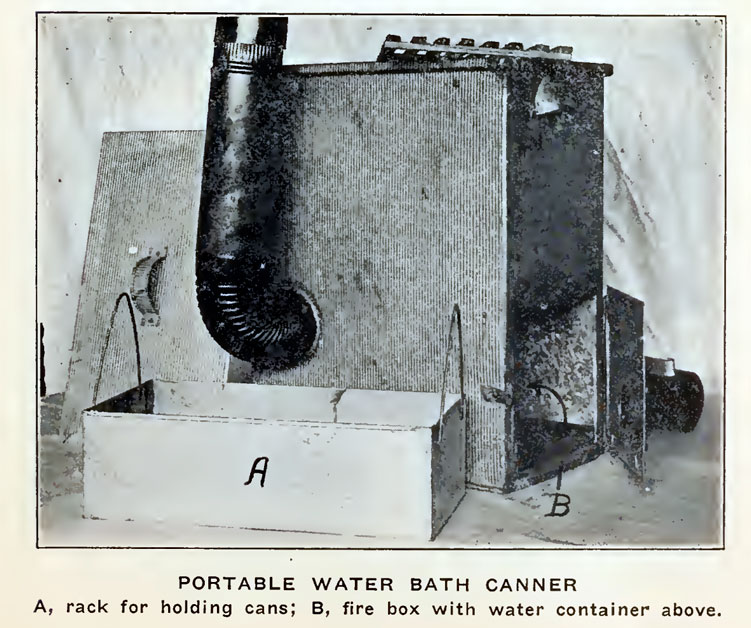

A portable water-bath canner from 1914, with its own smoke stack. Src: Stanley, Louise and May C. McDonald. The Preservation of Food in the Home. University of Missouri Bulletin, Vol 15, # 7, Extension Series 6. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri. 6 March 1914. Page 13.

What home canning products is water bathing used for?

Water bathing is suitable only for low pH food products, usually referred to as acidic. That’s foods with a pH below 4.6. [8] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. Accessed January 2015.

That’s many, though not all fruits (for instance, apples and blueberries are acidic; melons, bananas, and figs are low-acid), and pickled vegetable products.

“[We] recommend a short boiling water process for all of our pickled products if you are going to store them at room temperature. The boiling water process for pickled products only really works if you have a truly acidified vegetable that’s below pH 4.6 so for pickling and boiling water canning we really try to stress that people follow recommended recipes with canning times and that you don’t alter the proportions or ratios of vegetable to vinegar or acid to low-acid ingredients and assume a boiling water process might still work. Now if you work with someone who knows what they are doing, that’s another option.” [9] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 1:20:30. Accessed January 2015 at

Unless a food product being canned is acidic (either naturally or via added acidity), then it must be pressure canned. Most fruit jams are fine to water bath can; a relish or pickle is fine, apple slices and sauce are fine, pickled beets and pickled carrots are fine, but not carrots in plain water or beets in plain water — those must be pressure canned instead, and there is NO option allowed to water bath low acid foods such as those.

Water bath canning cannot replace pressure canning. Ever.

Water bathing can never replace pressure canning for products that need to be pressure canned.

A sad example was documented in 1953 in Grand Forks, British Columbia. Bottles of corn on the cob were boiled continuously in a water bath for 4 ½ hours. Before the corn was served, it was reboiled again for several minutes. Both people who ate it became gravely ill; both subsequently died — because the wrong canning procedure was used. We’ve known since at least the mid 1940s that corn must be pressure canned. [10] BC Centre for Disease Control. Botulism in British Columbia: The RISK of Home-Canned Products. October 2012; Revised January 2015. Page 4. Accessed January 2015. They could have boiled those jars of corn for 10 days, and it still would not have been safe.

We have had people reporting that they are still using boiling water canners — in one of our surveys it was as high as 30% — for canning vegetables, which puts them at high risk for botulism.” [11] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. 1:16:25. Accessed January 2015.

We still get quite a few folks call in who are water bath canning low-acid foods. The USDA deemed that unsafe decades ago .. so if you are water bathing, you are not necessarily killing the bacteria… the bacteria that can grow in low acid foods such as vegetables, meat, stews, they require a temperature of 240 F (115 C) degrees, you will never get to 240 F (115 C) degrees in a water bath, you will max out at 212 F (100 C), which is fine for high acid foods, not the case with low acid, it doesn’t matter how long you cook it on your stove, it’s not going to get to 240 F (115 C).” [12] Jessica Piper. Video: Canning Lids 101. 27:00. Accessed March 2015.

The water bathing pot

You can buy specially designed pots for water bathing; most pressure canners will also do double duty as a water bath canner.

You can instead use a pasta or stock pot if the height will be enough for the jars you have in mind, covered by water, and still be tall enough not to allow boil over. Dutch ovens are rarely tall enough unless you are using the 125 ml (4 oz) jars. To “test”, place the jar in the pot, and picture it covered by 3 cm (1 inch) of water, and then 3 cm (1 inch) of space above that to allow for the water bubbles.

The size of the pot might or might not matter; not enough research has been done: “Virginia Tech in the 1970s pointed out that small boiling water canners may not deliver the same level of sterility as large ones, but no follow-up research was done.” [13] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. Accessed January 2015.

You need some “padding” in the bottom of the pot when water bath canning

Something has to be at the bottom of the pot to prevent the jars from rattling about too much and as a result possibly getting broken. The “padding” also prevents extreme direct heat transfer, which could cause the jars to shatter.

The “padding” is usually a wire rack or trivet which raises the jars just a bit off the bottom of the pot. Such a device is ideal, because the space under it also helps allow for even heat circulation.

Failing that, if you are an occasional canner, some people suggest to try using a clean dishcloth as your padding. Many people report, however, how frustrating that is, because the cloth flaps about in the water, and often ends up tipping the jars over on their sides by the end of processing.

When calculating the height requirements for an improvised water-bathing pot, don’t forget to take this bottom “padding” into account.

Water bath in a covered pot

Do your water bathing with the cover on the pot for increased energy efficiency.

It is safe to water bath in an uncovered pot, but wasteful of energy.

Jar Sizes

You can use smaller size jars than indicated, but never larger size jars than indicated because they haven’t been tested for the longer heat penetration times.

Process smaller jars for the same time as indicated for the jars called for, unless separate times are given.

Example (1). A recipe says process pint jars for 15 minutes, with no mention of other sizes. This means you can also do smaller sizes, but they must be done for 15 minutes as well. You can’t do larger sizes.

Example (2). A recipe says pints 15 minutes, quarts 25 minutes. This means you can do pints or smaller sizes for 15 minutes processing; you can also do the larger quart size jars but the time on those is 25 minutes.

If you waterbath both size of jars at once — say 250 ml (½ US pint) for 10 minutes, 500 ml (1 US pint) for 15 minutes, be sure to have a kettle of boiling water ready as the water level in the water bath will drop on you when you remove the smaller jars 5 minutes before the larger jars, and you will need to top it up in a hurry.

As you get to know your water bath canner and various sizes of jars, you’ll learn how much water before the jars go in is too little and how much is too much — why you’ll have to learn is the effect of displacement upon the water by your jars. Until you know, it can be handy to have a full kettle of just boiled water at the ready in case you need to do a quick top up at the last minute when the jars are in.

When to sterilize jars before water bath canning

It’s a waste of time to sterilize your jars if your recipe calls for a water bath processing time of 10 minutes or greater. For processing times of 5 minutes (or anything under 10), the jars must be sterilized first:

If you are using a process time of only 5 minutes, such as for some jellied products, then you need to pre-sterilize jars before filling them (or increase the process time to 10 minutes, plus any altitude adjustments). If a process time is 10 minutes or more (at sea level) then will the jars be sterilized? Yes, but be sure to wash and rinse them well, and keep warm, before filling them with food.

Sometimes people choose to increase a 5-minute process time for certain jams and jellies to 10 minutes so that they do not have to pre-sterilize the jars. The extra process time is not harmful to most gels and spoilage should not be an issue as long as the filled jars get a full 10-minute treatment in boiling water. (And remember your altitude to increase this process time as needed.)” [14] Christian, Kacey. “Do I need to pre-sterilize my jars before canning?” Blog post at National Center for Home Food Preservation blog. May 2014. Accessed May 2015.

Jar Temperature

One of the principles in water bath canning is: “cold jars in cold water, warm jars in warm water, hot jars in hot water.” This compares the temperature of your jars (including their contents) with the temperature of the water they will be placed into for processing.

The reason for this principle isn’t for food safety per se: it is for safety during the processing procedure — so that jars don’t explode from thermal shock. [15]

Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 1:05. Accessed January 2015 at

In fact, it’s safest not to have the water at a full boil when you put the jars in:

- for hot pack food items, have the water in your pot simmering, around 80 C (180 F);

- for raw pack, have the water quite warm but not hot enough to simmer. That is about 60 C (140 F.)

Double-decking for water-bath canning

The answer depends on who you ask, let alone if it’s even physically possible for your equipment. See page on Double-Decking.

Water levels for water bath canning

The rule of thumb for how deeply the tops of the jars should be covered with water is [16] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 1:05:00. Accessed January 2015. 1:05 :

- 3 cm (1 inch) of water if 20 minutes and under;

- 5 cm (2 inches) of water if over 20 minutes because water will evaporate away.

[Tip: More water than 3 to 5 cm (1 to 2 inches) on top of the jar doesn’t help and is a waste of energy.]

[Further tip: Don’t forgot to allow for displacement of water by the jars you are adding! If you are processing just one jar, then you will indeed need just about the full amount of water that would be required to fill the pot to the required height. If you are processing a lot of jars at once, then you will need far less water because the jars will help to push the water up to the required height.]

On top of that, you need to allow 3 to 5 cm (1 to 2 inches) of “blank” headspace in the pot to allow for the surging of the boiling water (technically known as “walms.”)

So in summary, the pot you choose to use needs to be at least 10 cm (4 inches) taller than the top of the jars you are going to process in it (and again, don’t forget allowance for your bottom “padding.”)

The jars must be kept completely submerged under at least 3 to 5 cm (one to two inches of water) because you want air to escape (that’s why the rings go on snug but not crazy tight– so air can escape) and once it does, to not find its way back in.

“[It] has been documented since the 19 teens and 1920s that it does reduce the sterilization to not have the lids covered in water.” [17] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 37:54. Accessed January 2015.

What about not completely covering the jars in water? i.e. “Low-water level canning”

“In the 1970s there was some research into steam canning and low water level water baths (where the water didn’t cover the lids) because the first energy crisis had hit and there were concerns about how much energy pressure canning used, but the research was never completed.” [18]Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013.

“Back in the 1970s, some people were actually trying to see if you could use a boiling water canner as is, but maybe not have the water over the tops of the jars like we currently recommend. For example, maybe only half-way up the sides of the jars. So that’s what they were looking at, when they were just looking at low-water level canning. Trying to see if you could sterilize the food in the jars without covering them in boiling water. And just FYI, they showed that you really can’t do that. That had also been documented way back in the 19-teens and 1920s using some different jars and canners that were available back then but they came to the same conclusion. That it did decrease the sterilization of the process to have the water too low….. We don’t have any recommendation for low water level canning and I’ve never seen any come out that are truly research-based to endorse that. What happened with the research in the 1970s is they modified the typical situation enough in their data collection that no — processing experts do not believe that the data they came up with would reflect what people would actually be doing at home so they couldn’t endorse the recommendations from that study.” [19] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. At 37:00. Accessed January 2015.

Water bath times

Any cooking time of the food while you are preparing it to go into the jar does not count towards processing time of the bottled food product. The water bath processing time is counted completely separately from any previous cooking time involved in the recipe.

The processing time counting only starts after the jars have been placed in the pot of boiling water AND the water has reached / returned to a full boil.

A blogger notes this:

One other thing we thought of that quite a few folks have done wrong, including my oldest son, Bill, is to begin counting the processing time in a water bath canner from the time they put the jars into the canner. This is wrong and can result in failed seals, mold, or fermenting foods. The time should always begin when the canner full of jars comes to a full rolling boil.” [20] Clay-Atkinson, Jackie. Avoiding common canning mistakes. Backwoods Home Magazine. Issue #142, July / August 2013. Accessed January 2016.

At sea level, typical water bath processing times are anywhere from 5 to 15 minutes (with 5 minute processing times becoming less common now in recipes.)

What could take over 20 minutes in a water bath at sea level? Sauerkraut for instance (20 minutes for ½ litres / US pints; 25 minutes for litres / US quarts).

Altitude increases time required for water bath

The altitude that you are working at affects water bath canning, in that it increases the processing time required.

“It doesn’t increase the temperature, because you can’t with boiling water, and it doesn’t increase the amount of water needed to cover the jars, it just increases the time required.” [21] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. Accessed January 2015

See the chart, “Altitude Adjustments for Water Bath Canning.”

Minimum canner load for water bath canning

As of 2016, no reputable source has stated a desired minimum canner load (minimum number of jars) for water bath canning.

HealthyCanning is aware that a few researchers have mused about such research possibly being of interest one day. The reason would be that jar load in a canner would affect the come-up to temperature times before the start of processing.

Rest your jars in the canner after water bath processing

When the water bath processing time is up, turn the burner off, remove the lid from the pot, and set a timer for 5 minutes.

Water Bath Wait Time: 5 Minutes. These new waiting time recommendations were added to improve lid performance and reduce sealing failures. These directions should be added to canning procedures for all products. In 2006, water bath canning directions were updated, advising consumers to ‘Wait 5 minutes before removing jars’ to be consistent with a major canning lid manufacturer’s advice based on their research on lid functioning and seal formation. ( When using a boiling water canner: ‘After jars have been processed in boiling water for the recommended time, turn off the heat and remove the canner lid. Wait 5 minutes before removing jars from the boiling water bath canner.’)” [22] University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Home food preservation: Up to date canning practices. Accessed May 2015.

..wait 5 minutes (this is a recent addition to recommendations, based on what the jar and lid makers were saying.) This step is not for food safety, but it’s to help prevent contents of jars boiling up or over when moved to a colder spot, and therefore get a more assured vacuum seal.” [23] Andress, Elizabeth. “History, Science and Current Practice in Home Food Preservation.” Webinar. 27 February 2013. Accessed January 2015 at

If boiling hot jars were to be subjected to immediate cooling, a sudden rush of food out of the jars (called “siphoning”) could occur.

The five minute time for the jars to settle a bit also provides a bit more safety for the operator doing all this.

On the other hand, don’t let the jars stand for hours afterward in the canner, or your food products may develop flat sour.

Removing the jars

Don’t tilt the jars because it may cause food product or jar liquid with food particles in it to come between the as-yet unsealed lid, and the rim of the jar, preventing a seal.

Don’t sit the jars near a cold draft, you want them to cool slowly and evenly. Whenever you put them, leave them untouched for 12 to 24 hours. Especially do not adjust rings during this time. [Note: the exception is for Tattler lids.]

Do not turn the jars upside down; it’s voodoo canning. The old belief was that that helped with the seal, but statistically it’s been proven to actually increase seal failures. Dance around your jars in a grass skirt instead, if you wish: at least it won’t interfere with the sealing.

Discredited variants of water-bathing

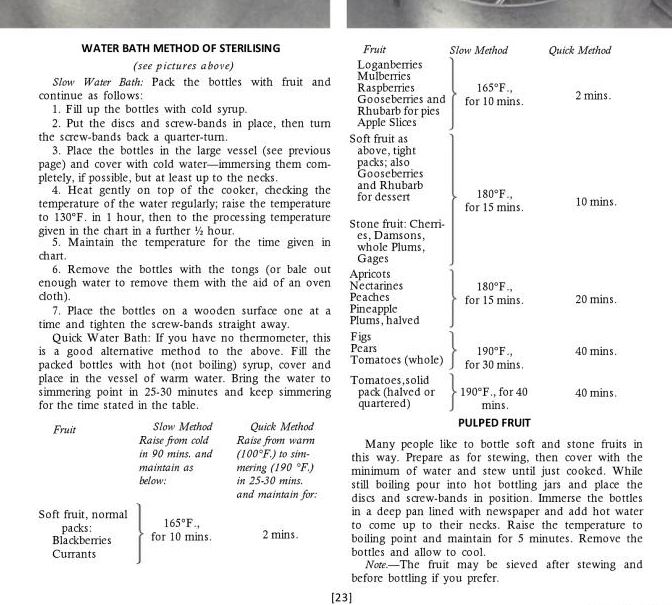

An English writer, John Harrison, cites a “Slow Water Bath Method” and a “Fast Water Bath Method.”

Slow: place filled jars on rack in pot. Cover jars with cold water, place lid on pot. Gently heat the water so that it reaches a temperature of 55 C (130 F) for over an hour… [then] turn the heat up a little and bring it up to the recommended temperature over the next half hour… Once at the correct temperature, hold for the required time…”

Fast: place filled jars on rack in pot. Cover in warm water. Bring the temperature up to simmering point over half an hour and then hold as per the chart on page 44. After this time, treat exactly as the slow water bath method processed fruit.” [24] Harrison, John. How to Store Your Home Grown Product. London: Constable and Robinson. 2010. Chapter 7.

The information he presents in his 2010 book doesn’t appear to be original to him. It appears to be lifted straight from this 1960s Good Housekeeping Leaflet.

These ideas about water bath canning are now more than 50 years old and are not endorsed by modern canning authorities. Follow the water bath processing instructions in modern recipes: they are simpler and faster, to boot.

Online Learning

University of Minnesota: online water bath canning tutorial.

Further reading

Boyer, Renee R. and Julie McKinney. Boiling Water Bath Canning: Including Jams, Jellies, and Pickled Products. Virginia Cooperative Extension. Publication 348-594. 2013. (Link valid as of March 2015.)

Stolpa, Debbie and Marily Herman. Boiling Water Bath Canning. University of Minnesota Extension Service. 2010. (Link valid as of January 2015.)

References

Janelle

It had been awhile since I canned and I had forgotten to fully submerge the jars in a hot water bath. The jars and lids were pre-sterilized and remained in a water bath during filling with a star fruit strawberry jam. The filled jars were then placed in pots that and been filled with water over halfway up the jars and brought to boil while covered. It has been several days since I canned them and they have been at room temperature. Any chance they can still be safely consumed? Would doing another (proper) hot bath be a solution?

Thank you for any insight.

Corlissa

I think I really need clarification on Water Bath Canning. I’m just delving into the world of home preserving and confused as the what this term really means. I was taught how to can by my mother and have never actually done it on my own. If I hadn’t accidentally found an instruction on a downloaded recipe this week I don’t think I would have ever realized that I might not be practicing safe canning methods. I was taught that water should only come up to the bottom of the threads or the bottom of the ring, NOT that it should cover the entire jar by 1-2 inches. What is the science for covering vs, nearly covering with water for processing? I/We have always processed according the length of time at a full boil, but never with the seal and rings submerged. Will this still allow the spores and other harmful organisms to be destroyed?

Healthy Canning

See above section on water levels. “[It] has been documented since the 19 teens and 1920s that it does reduce the sterilization to not have the lids covered in water.”

Susan Dashiell

I have a question about canning organic apple juice. Why is it necessary to heat the apple juice to 180 degrees when you water bath the jars in a boiling canner for ten minutes? Wouldn’t the 212 degrees temperature do the same as the pasturizing process?

Healthy Canning

There’s a lot of difference in procedures, so you’ll want to pick one and follow. There’s quite a few differences, really. (Note that none of them say 180 F, it’s 190 F.)

The Ball Blue Book (2014), and the Ball / Bernardin Complete Book (2015) and Bernardin Guide (2014) all call for apple juice (and grape juice) before canning to be brought to 190 F (88 C) and held there for 5 minutes, with a caution not to let it boil. [Those directions would pretty much require something like a candy thermometer clipped to the pot, and for you to watch the heat like a hawk during those 5 minutes.) The Blue Book says process pints or quarts or half-gallons for 10 minutes. Ball / Bernardin Complete, and the Bernardin Guide, allow for quarts / litres only, 10 minutes.

The USDA Complete (2009) and So Easy to Preserve (2015) both call for simply bringing the juice just to the point where it just starts to boil, then canning it. Pints and quarts (1/2 litres and litres) are then 5 minutes; half-gallons (2 litres) are 10 minutes.

As for the USDA and So Easy to Preserve directions, I would think this: that the processing times are based on the apple juice going into the jars piping hot, and that if the juice wasn’t piping hot, the processing times would have to be longer, perhaps substantially, but that’s not what they tested. They tested piping hot juice into jars, 5 minutes for the two smaller juice sizes, 10 minutes for the big honking size. NOTE though the because the processing time for the two smaller jars is only 5 minutes, those two jars must be sterilized first: it’s only jars being processed 10 minutes or more that no longer need to be sterilized (you probably know that, just being thorough.) To avoid that, you could just increase the processing time to 10 minutes, as Ball and Bernardin have.

You would need to ask Ball / Bernardin what they are trying to achieve there by asking for a 5 minute hold at that temperature. Note that they also call for longer process times on the 2 smaller sizes than do USDA or So Easy to Preserve, but that could be to avoid jar sterilization.

You may wish ask the National Center for Home Food Preservation what the science behind their recommendation actually is; you could also ask Ball and Bernardin, though they are less likely to give you explanations beyond ones you probably already know.

I haven’t done my apple juice yet this year, as I’m waiting for apple bushels to hit the right price… but I’ll be following the USDA / So Easy to Preserve directions as those directions are less fussy (don’t have to watch a thermometer), and on the 1 quart / 1 litre jars, I’ll increase the 5 minutes processing to 10 minutes processing to avoid the futzing of sterilizing jars. (You’ll allowed to increase processing time, but never decrease it.)

Note that you can now also use a steam canner to process your jars of juice in, to save time and energy. I’ll be doing that. I am starting to think that perhaps the faster “come up to speed” times are also gentler on food items than a water bath.

Whatever you do, I personally would pick one tested, guaranteed procedure, and follow it.

Hope this helps or at least points you in the right direction for further thinking / research.

Side point of interest, apple juice (and grape juice) are currently the only approved items for canning in the 2 litre (half-gallon / 2 quart) jars.

p.s. You probably know, but the organic aspect doesn’t factor into the canning safety equation at all, sadly. And the idea is not to pasteurize but to go beyond that, and sterilize, for shelf-stable, sealed storage. Many moulds and many nasties need higher temperatures than sterilization to knock them off. You don’t even want how much bird poop falls on those apples out in the orchard…. :}