In the home canning world, the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) plays a dominant role. In fact, most home canning authorities would describe it as “the center”.

All reputable sources of home canning recipes and directions will defer to the core canning safety advice provided by the USDA.

- 1 What is the USDA?

- 2 In the canning world, what do people mean when they refer to the USDA?

- 3 The USDA ‘canning people’ would probably love to spend more time researching the questions we have

- 4 The USDA is considered the leading expert in home canning

- 5 USDA Extension Agents

- 6 The USDA won’t guess

- 7 Criticism of the USDA

- 8 Is the USDA too strict?

- 9 Is the USDA loved or hated?

- 10 Brief history of the USDA’s role in home canning

-

11

History of USDA Canning Publications

- 11.1 USDA Canning Publications (1909)

- 11.2 USDA Canning Publications (1917)

- 11.3 USDA Canning Publications (1921)

- 11.4 A pause for change in approach and science (1920s to 1930s)

- 11.5 USDA Canning Publications (1936)

- 11.6 USDA Canning Publications (1942)

- 11.7 Agricultural War Information (AWI) publications (1943- 1945)

- 11.8 USDA Canning Publications (1946)

- 11.9 USDA Canning Publications (1947)

- 11.10 USDA Canning Publications (1952)

- 11.11 USDA Canning Publications (1977)

- 11.12 Recent times — USDA Complete Guides (1988 – onwards)

- 12 Related reading

What is the USDA?

The USDA is the United States Department of Agriculture, established in 1865.

It is a massive government department, with over 100,000 people in over 33 different sub agencies and departments (as of 2016), and a projected budget (2017) of approximately $150 billion US. [1] USDA FY 2017 Budget Summary. Accessed June 2016 at https://www.obpa.usda.gov/budsum/fy17budsum.pdf

In the canning world, what do people mean when they refer to the USDA?

When people in the home canning world refer to the USDA, they are referring to the USDA funded efforts to help home canners since 1909.

It’s important to note that those efforts do not by any means involve all 100,000 people and all the $150 billion dollars.

In fact, the USDA’s home canning ‘arm’ is extremely, extremely small.

The USDA’s central home canning efforts are directed through the National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP) in Georgia. Sounds grand, but, as of 2016, there’s actually only one person there, and, that’s only part of her work: she also has to do work for the University of Georgia.

The NCHFP acts as the hub of a wheel.

The spokes of a wheel are the ‘Extension Services’ at universities in various states. These Extension Services act as knowledge transfer agents, to ensure that knowledge from the academic world is transferred in an applied, practical way out into the surrounding world.

The USDA directs funds to help with home canning through these Extensions. These would be people who are part-time, or, whose full-time job is actually something else, with just a portion of their work week or year being funded for home canning matters. We’re never seen a tally on how many funded or partially funded positions per University Extension, but it’s likely less than a handful per.

The funding for all parts of the wheel is bare bones.

So, when in the canning world we talk about the “USDA”, we are talking about a network consisting of a small handful of people who, like Mulder and Scully in the X-files, care passionately about a small field that everyone else in the massive mother organization likely thinks is “weird”, so they are relegated to the “basement office” with hand-me-down furniture and a bare trickle of funding to make sure the lights come on when they flick the switch in the mornings. There are likely many community centres, golf clubs and parish church offices that have greater and more secure funding to work with than these people do.

Still, Americans need to be grateful: America is the only country in the world that funds any knowledge transfer at all like this for home canning.

In any event, when home canners refer to “USDA canning people”, these are the people they mean.

The USDA never approves canning-related products or supplies. They will cite products as an example. And, they will positively recommend FOR practices, procedures and principles. And rarely, come out and explicitly recommend AGAINST something. (See USDA Recommendations for and against .)

The USDA ‘canning people’ would probably love to spend more time researching the questions we have

These “USDA canning people” are caught in the middle, and probably frustrated. Under-staffed and under-resourced, they scramble to answer questions from 300 million Americans and keep them from wiping out their churches and neighbourhoods with botulism from using 70 year old canning books with dangerously out-dated advice.

At the same time, some home canners criticize them for being “behind on consumer demands” and not having researched more pressure canning recipes using tofu and soy milk to keep up with changing tastes and changing times.

The “USDA people” would probably love to research a lot more things such as that, and faster too (even if people didn’t always like the answers.) They probably would have loved to get an answer out about steam canning decades ago. Finally approved in 2015, it had been a question since at least the 1920s, according to Elizabeth Andress. [2] Andress, Elizabeth L and Gerald Kuhn. Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. IV. Equipment and its Management –

History and Current Issues Team Canning. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, Cooperative Extension Service. 1983.

It’s an old truism that governments seem to be able to find money for everything, except anything useful. The great body of the home canning research that we work from today was done with a small investment from the government in the 1940s — particularly 1943 to 1946, when food was used as a war weapon by the Allies. Most people would argue that that was a very good use of tax-payers’ money: in the decades since, it has generated and continues to generate a massive return on investment in terms of social capital, household economy, and population health. Very little if any of government money spent in any of the decades since then is still delivering such a return, let alone any return at all.

While many home canners criticize the ‘USDA people’ for not keeping up, it’s possible we all keep missing the clues they have been trying give us. Those people obviously can’t say in public, “tell our USDA bosses at the top to give us a bit more money to research some of this stuff you guys want.” They’d get a strip torn out of them, and maybe lose their jobs. Instead, they say things such as “Currently we have no recommendation for doing that and currently there is no funding to research it.” That’s probably as clear as they dare to say, “we’d love to but we don’t have the funding — but you could tell your elected representatives you want that situation to change.” But home canners seem to get angry with them for the first part of that sentence, and not twig to the pretty clearly implied second part.

The USDA is considered the leading expert in home canning

The USDA is considered the leading expert in home canning by both the private and public sector.

Outside of America, the USDA’s home canning knowledge is also very widely respected, and is cited as the international authoritative source on home canning. The Canadians, as just one example, acknowledge their authoritativeness, in French and English:

Reliable sources of scientifically-validated home canning recipes and detailed processing instructions include the: USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning from the United States Department of Agriculture” [3] Province of Ontario Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Rural Affairs. What you should know if you’re home canning. Accessed March 2015.

« Les États-Unis sont vraiment des pionniers avec les informations pertinentes et scientifiques sur les conserves maison. C’est le USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) qui a vulgarisé les conserves domestiques, depuis la ‘Grande Dépression’ autant qu’en propagande de guerre.» [4] Vincent le Canneux. Le Forum des Conserves Maison. Poste le 14 octobre 2013. < https://www.conserves-maison.com/viewtopic.php?f=13&t=3886 > (mars 2015)

This is not to say that the USDA is the only expert. Home canning is an evolving science, and, by virtue of minimal funding to the USDA’s home canning research area for the past several decades, their research in some aspects may now well lag behind more current science-based findings out there in the field by industry and private-sector partners such as the Jarden home canning companies. As a home canner, when trying to identify what qualifies as a reputable source for home canning information, just be sure to verify that a source can point to science-based, lab-tested research results to back up their information.

USDA Extension Agents

The people that the USDA helps fund at various University Extensions across the country are often referred to as “Extension Agents.”

Some of these people can sometimes tend to be very conservative in their advice. Many won’t even admit that you are safe to add a shake of oregano to your home canned tomato sauce. They are sometimes be a bit behind in their knowledge, too: in 2016, many are still saying that steam canning is “not recommended” (It was in fact approved by the National Center in June 2015), and are saying that heritage tomatoes are more acidic than modern tomato varieties.

A few are scientists and seem to be lucky enough to actually get some funded time to keep up with the latest news and even help move things forward. Most though appear to be educators who may be so run off their feet educating that they don’t always have time to keep up with the latest and greatest.

Rick Heflebower and Carylyn Washburn, professors at Utah State, explain:

Extension agents are educators by profession. Their mission is to teach ‘research based’ methods to the public. For various reasons, rumors or opinions are spread around as though they are truth, such as the notion that ‘older tomato varieties are more acidic than newer hybrids’ and therefore safe to can without acidifying agents. In our study, the tendency was for the older varieties to be less acidic than the hybrid we compared them to. Advice is sought from Extension agents each season regarding which tomato varieties to grow successfully and how to safely process them. We feel that it is important for Extension agents to promote the current USDA recommendations and to understand them well enough to advise others.” [5]Heflebower, Rick and Carylyn Washburn. The Influence of Different Tomato Varieties on Acidity as It Relates to Home Canning. Journal of Extension. December 2010. Volume 48 Number 6. Article Number 6RIB6. Accessed June 2016 at https://www.joe.org/joe/2010december/rb6.php

So if you do hear advice from an Extension Agent, or an entire Extension Service, that appears dated because the National Center has issued an update on something, it could simply be because they are run off their feet teaching current material and haven’t had the occasion to refresh yet.

The USDA won’t guess

Many times people ask the USDA people to “guesstimate” a processing time for something they desperately want to home can.

The USDA will not guess. They are not being obstinate. The fact is, they already played that game in the early days — and people were dropping dead like flies.

Much canning advice, up until about 1920, was based on individual experiences rather than scientific determination.

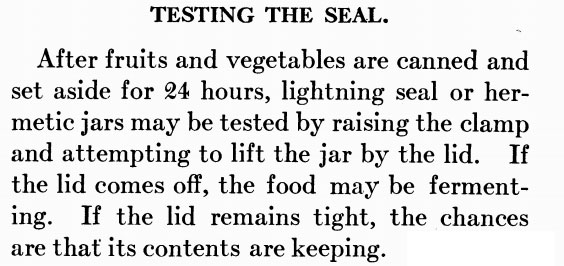

Here’s some USDA advice from 1917 / 1918.

Creswell, Mary E. and Ola Powell. Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables. USDA. Farmers’ Bulletin 853. July 1917; revised 1918. Page 7.

Notice the end phrase: “chances are that it contents are keeping.”

Chances are. Anyone used to today’s modern 190% “safe and sound” guarantee from USDA home canning recommendations would fall out of their seats reading that. It would absolutely not be acceptable; people wouldn’t stand for it.

A USDA scientist, Charles Ball, in 1927 summed up the USDA’s approaches as being “cut and try”: keep canning something with different processing times until it stopped going bad in the jars. (For more detailed information, see Early History of the USDA.)

During the war, with shortages of proper equipment, some extension agents tried to be helpful by suggesting very long boiling water processing times for foods that the USDA overall already knew had to be pressure canned instead to be safe. And people got sick.

Those days of trying to be helpful, with not very good results, are long gone.

They wouldn’t get any thanks anyway, if their guess happened to be right. And if they were wrong, they’d be in a lot of trouble legally these days, and the people involved in the guess would lose their jobs. So there is just plain no upside in a guess for them.

Besides that, they are too dedicated professionally to their field to do something as risky as guessing, regardless of the upside or downside. Their stance on canning plain cabbage from the National Center’s blog sums it up:

“… we do not just guess at a process time – the risk is too great. So I’m sorry to disappoint, but we do not have a recommendation for home canning cabbage as is. We currently do not have the resources to conduct individual product testing, and we do not know of others looking to do so at this time.” [6] NCHFP blog comment 23 January 2015. Accessed March 2015.

Criticism of the USDA

Home canners in other countries are in awe of the level of advice and support that has come from the USDA for home canners.

Americans at times can seem a bit less appreciative, perhaps proving the old statement, “a prophet is not without honour, but in his own country.”

People who want to do their own thing in home canning, and who encourage others to follow their particular teachings (and buy their books), get very cross at the USDA. They want to promote their methodology over the USDA’s:

The USDA doesn’t trust home-canners to do things right, and so their way to compensate for it is to tell you to cook the hell out of everything — and it produces low-quality canned goods…The USDA will tell you to never use an heirloom recipe. I think they just don’t trust people to be smart enough to do it right…. a lot of the most common things you’d make don’t even require a water bath canner — you can use the inversion method.” [7] Hillary Cherry in: Jackman, Michael. How one Hamtramck woman preserves home canning know-how. Detroit, Michigan: Detroit Times. 13 August 2014. Accessed March 2015.

Other people take the USDA’s canning advice personally:

I am also a person of science (nurse) and I find the [USDA] insulting. They use ‘research’ to make it more difficult for us to take care of ourselves. They also twist and use single statistics out of context to scare people to death.” [8] Comment on Hill Billy House Wife blog. Accessed March 2015.

A perhaps more balanced criticism is how the USDA’s recommendations are given. There are people who say they are happy to and do follow the recommendations, but who would still just like to know the why. The old school USDA approach since World War Two, they feel, has been very much school marm: never mind the why, just do as you’re told. This has had the effect of getting Americans’ backs up, and Americans historically have never been at their most cooperative in such a condition. It has also had the effect of causing people to do internet searches on the “why”, and they often find dangerous, conflicting advice as part of the answer.

Part of the reason for the lack of detailed reasons behind directions is surely a simple lack of time: there are so few people actually working in home canning for the USDA that they barely have time to find and hand you the right recipe from the store chest of tested recommendations and recipes that they have to work from, let alone sit down with you and go over it, as there can be 500 other new email queries to answer that day.

The underlying issue, though, might be that original writers of those recipes and recommendations did not take the time, or feel it necessary, to separate out quality versus safety reasons in the directions. For instance, the canning recipes for tomatoes all direct you to peel the tomatoes first. Was that just a personal preference of the original recipe writer? Turns out, peeling tomatoes for home canning is a safety reason. But the directions don’t say.

One blogger writes,

The USDA has done a tremendous amount of research on home canning. They do not approve or disprove anything but rather make recommendations based on the results of their research. They may not recommend using a certain ingredient (eg. corn starch) or canning a certain food (eg. broccoli) because the resulting quality is less than acceptable. They may not recommend canning a certain food (eg. thickened stew, pureed pumpkin) because it presents a safety issue as the heat cannot penetrate to the centre of the jar to ensure a safe product. The problem is, the USDA does not disclose whether their recommendation is based on safety or quality.” [9] https://momskitchencooking.blogspot.ca/2013/10/where-are-canning-police-when-you-need.html#sthash.6HzkQSLS.dpuf

At various times in the past, USDA educators have tried to help people being understand the reasons behind canning recommendations:

In 1921, a USDA writer wrote:

“SUCCESS in home canning depends a good deal on how well the canner understands the ‘why’ of each step in the method. For that reason and because of an increasing interest in and demand for such information, this bulletin goes more thoroughly into the science of canning than would ordinarily be justified in a popular discussion of how to can. The reader who wishes to turn at once to directions for canning will find them beginning on page 14.” [10] Home canning of fruits and vegetables. USDA Farmers’ Bulletin 1211. 1921. Foreword.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the USDA funded regular radio ‘chats’ to pass on detailed background information, tips, and the latest news about home canning.

The lack of detailed reasons today may go back to the current funding situation: there simply just may not be the funding to explain the rationale.

One other frequent criticism of the USDA is as follows: for food items that might take so long to process safely that consumers might not like the result at the end, the USDA testers may have simply decided not to release the results. Some people feel that rather than make that quality decision themselves, which can be subjective (for instance, some people love canned turnip, others do not), that the USDA should have released the processing times to people with an advisory about quality, and let people decide themselves.

Healthy Canning isn’t currently aware of the USDA having any such completed and safe-but-dubious-quality testing results they are holding back on. Ball, however, does: Ball had and then withdrew in 1977 canning advice for broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, celery, and cabbage. Previous to withdrawing those canning recommendations Ball had warned about quality. If you are interested in the reason for the withdrawal, it’s Ball you would need to ask: the USDA never had issued canning recommendations on those products.

Is the USDA too strict?

One criticism often levelled at the USDA is that they are too strict. People who say that need to meet Bernardin, which oftentimes exceeds USDA standards to be stricter and more rigid on some matters. Among other things, Bernardin won’t let you play with pickling lime at all [11]Kingry, Judi and Lauren Devine. Ball / Bernardin Complete Book of Home Preserving. Toronto: Robert Rose. 2015. Page 289 while the USDA will, and Bernardin doesn’t trust all apples to be reliably acidic enough on their own for applesauce and thus requires you to acidify it:

Adding sugar to applesauce is optional…. However, lemon juice is not an optional addition. Lemon juice is added to help preserve the apples’ natural colour and to assure the acidity of the finished product, since different varieties and harvesting conditions can produce apples of lower acidity.” [12] Kingry, Judi and Lauren Devine. Bernardin Complete Book of Home Preserving. Toronto, Canada: Robert Rose Inc. 2015. Page 182.

So strict is relative — and this is just to say, there are stricter out there. The USDA does try to reason with people and give some leeway when it possibly can.

Is the USDA loved or hated?

For their work and the practical, safety advice they provide to home canners, the department is either respected, tolerated or… disliked.

While some home canners will gush about their Ball Blue Books, the fan club for quieter, plain USDA Complete Guide is less vocal. The Complete Guide is certainly less glitzy than some other canning books, with no full colour photos on glossy paper. That being said, though, tens of thousands of people use the USDA Complete Guide as their primary canning book, and swear by the delicious, quality, award-winning results that the recipes actually do deliver.

It’s important to bear in mind, too, that some people’s views of the USDA’s more primary activities (everything from farm subsidies to herbicides) can often so strongly colour their opinion of the USDA in general that the handful of people working on home canning may unfairly bear the brunt of their wrath at times.

Brief history of the USDA’s role in home canning

The USDA came into being on 15 May 1862 when Abraham Lincoln signed the Agricultural Act of that year.

The USDA’s involvement in home canning started in the very early 1900s:

Since the late 19th century, the USDA has published recommendations for home canning processes, pickling of foods, and sugar concentrates (jam and jelly products). Since that time the public as well as the Cooperative Extension System and home canning equipment manufacturers have continued to rely on the USDA for guidance. Scientifically-based methods for control of bacteria and calculation of sterilization processes for canned foods were developed in the first part of the 20th century. These methods and later refinements have been applied to the science of USDA home canning recommendations since the mid-1940s.” [13] Andress, Elizabeth. Current Home Canning Practices in the U.S. National Center for Home Food Preservation. Paper 46B-3. Presented at the Institute of Food Technologists Annual Meeting Anaheim, CA, June 17, 2002. Accessed March 2015.

In 1917, the USDA determined that pressure canning was the only safe method of canning low-acid foods without risking food poisoning [14] Presto Company History. Accessed March 2015. and began advising people so.

In the 1920s and 1930s the USDA put a lot of effort into educating the public on home canning.

When World War Two broke out, the USDA was told to pull out all stops in encouraging home canning in order to free up food for the troops, and they did.

There was so much to be done, that it couldn’t all be monitored closely, and various agents of the USDA may have had more zeal than knowledge at times. Some risky advice was given at times, apparently.

They allowed for the processing of plain beets in a boiling water bath if you added a tablespoon of vinegar to each pint jar (and indicated that it might be a method preferred over pressure canning, because it preserved the beets’ colour better.) [15] Cameron, Janet L. and Mary L. Thompson. Canning for the Home. Bulletin No. 128. Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College and Polytechnic Institute and the United States Department of Agriculture, Cooperating Extension Division. Revised June 1944. Page 10.

A higher up in the USDA Home Economics Bureau, Dorothy Shank, referred North Carolina extension agent Ruth Current to a bibliography containing Pamphlet #39 (Simplified Methods for Home and Community Canning) which advised the water bath canning of green beans as an option [16]Page 6 of Simplified Methods for Home and Community Canning. [17] Shank, Dorothy E. In Charge of Food Utilization Investigations. USDA Bureau of Home Economics. Letter to Ruth Current, Extension Agent in North Carolina, 18 March 1943.

Linda Ziedrich, author of The Joy of Pickling, thinks that painful memory of wartime mistakes is what makes the USDA “overcautious” (as some say) today:

Home canning reached a peak during World War II, when the US government commandeered 40 percent of commercial pickle output for the armed forces. Extension agents promoted food preservation along with Victory Gardens, even going so far as to divert steel from the munitions industry to pressure-canner production. ‘Novice canners were using shoddy wartime equipment also produced a record number of disasters,’ writes Harvey Levenstein (Paradox of Plenty, 1993). ‘Innumerable stoves were ruined, kitchens were splattered, and victims were hospitalized with severe burns, cuts and botulism.’ If US Department of Agriculture (USDA) guidelines today seem to be based on the assumption that the typical home canner won’t follow half of them, this history should explain the government’s conservatism.” [18] Ziedrich, Linda. The Joy of Pickling. Boston, Massachusetts: The Harvard Common Press. 2009. Page 5.

By 1944, 70% of American households canned fruits and vegetables, with most of them doing at least 100 to 200 quarts a year. [19] Andress, Elizabeth L. Research and Education in Food Preservation. Powerpoint presentation. 19 October 2014 at Food & Nutrition Conference & Expo, Atlanta, Georgia. Slide 4.

The war left the USDA cautious both about its own advice, and the level of optimism it should have in Americans to follow that advice.

After the war, refrigeration became more common in American households and the need to preserve everything through canning became a bit less urgent. Then home freezing came along thanks to Clarence Birdseye, and from the mid-1950s onwards, the USDA stopped “investing” in education for home canning and switched the focus to home freezing advice instead.

The USDA re-enters the home canning field

In the 1970s, households that canned fruits and vegetables in the States had fallen to only about 30%, and the majority only canned smaller amounts [20] Andress, Elizabeth L. Research and Education in Food Preservation. Powerpoint presentation. 19 October 2014 at Food & Nutrition Conference & Expo, Atlanta, Georgia. Slide 4.. People had switched to stocking up their chest freezers instead. However, with a “back to the land” movement leading to increased home canning (and illnesses) again, the USDA decided it needed to look at home canning once more.

In response to a massive return to home gardening and home canning in the mid-1970s (during the energy crisis) we began a systematic investigation of proper and safe methods for preserving fresh produce,” Dr. Gerald Kuhn, professor of food science, said.” [21]Penn State University offers free home canning and freezing guide. Greenville, Pennsylvania: Record-Argus. 23 September 1987. Page 5.

Consequently, in the first half of the 1980s they undertook a survey of home canning as it had been practised in the 1970s, and in the early 1980s. [22] Andress, Elizabeth. Current Home Canning Practices in the U.S. National Center for Home Food Preservation. Paper 46B-3. Presented at the Institute of Food Technologists Annual Meeting Anaheim, CA, June 17, 2002. Accessed March 2015.

After the survey, they realized that over the decades there had been various bulletins and pamphlets written for the USDA by various people with conflicting (and increasingly dated) advice — and some guesses.

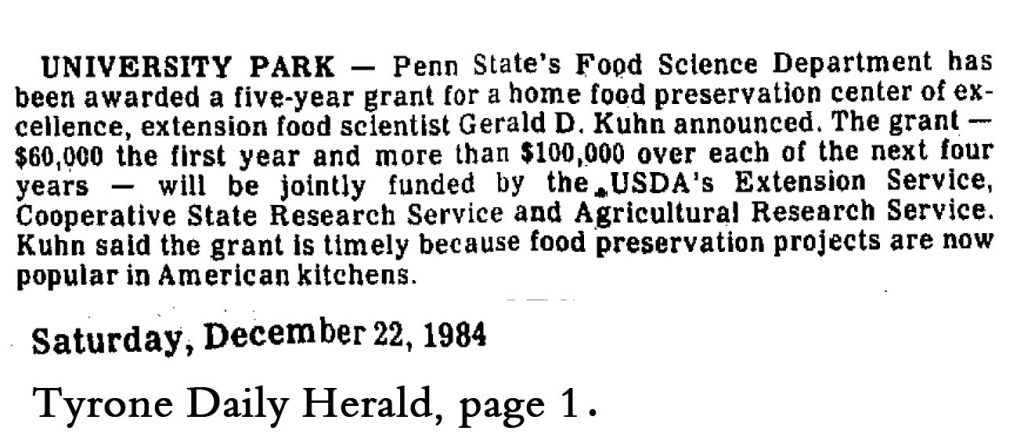

In 1984, Penn State University was awarded a five-year grant from the USDA to start a home food preservation center of excellence under Dr Gerald Kuhn.

Here’s an article from early 1985 about the new center:

PSU center plans study of canning

UNIVERSITY PARK – Home canning done correctly can remind us in the middle of winter of the sweet taste of our garden harvests. Done incorrectly, a hostess could be serving up a trip to the hospital when she puts last fall’s spaghetti sauce on her table.

Illness stemming from eating home canned food is unnecessary, and researchers at Pennsylvania State University — considered the leading authorities in the field of understanding home preservation — are striving to do away with the outdated and unsafe methods of food storage and preservation that cause it.

Because of its recognized leadership, the University’s Food Science Department has been awarded a five-year grant to establish the first Home Food Preservation Center of Excellence in the United States. Funding to operate the center totals $80,000 for the first year, and more than SHW, (HH) in each of the next four years. It was jointly offered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Extension Service, Cooperative State Research Service and Agricultural Research Service. “It is an awesome responsibility in terms of the services we will be asked to perform.” says Gerald D. Kuhn, professor of food science and project leader. “We will have this become the national base of information for our peers, and for consumers, through the extension service.”

Kuhn says Penn State began studying home preservation techniques in the mid-1970s, when home canning regained popularity after it was lost as a family art in the 1950s. “Valuable publications on the matter ceased in the ‘50s.” he says. Interest died off until 1975, when the energy crisis took hold and gardening became popular again. Gardeners renewed interest in preserving their harvests. However, the methods the preservers were using were suspect.

” Anything is safe — put it in a jar and put a lid on it,” Kuhn explains is the concept many preservers were using. This naturally led to outbreaks of bacterial problems and increased cases of botulism. “We still have outbreaks of botulism.” he says.

“Many changes have occurred during the last 20 years in terms of horticultural varieties, canning ingredients, equipment, home kitchens, lifestyles and preferences for foods.” Kuhn says. That is what the Penn State Center of Excellence team will be studying.

Working with Kuhn are Dr. Sudhir Sastry, assistant professor of food engineering; Dr. Stephanie Doores, assistant professor of food science; Elizabeth Andress, research assistant; and Thomas Dimick, senior research technician.

The team currently is working on venting practices and how they alter heat penetration, as well as a jar lid evaluation. In the summer, as the center is moved into its own facility and receives its computerized data acquisition system, the team will study several priority issues in the field, Kuhn says.

The team will review equipment, including dial and weighted pressure gauges, and the use of pressure cookers, as well as the reevaluation and establishment of processes for various foods which need new data bases. Kuhn says. The foods cover a wide range, and include asparagus, spinach, corn, peas, ground meat, heart, tongue, soup stock, rabbit, all forms of tomato products and combination products.

Miscellaneous projects will include special diet requirement foods, pie fillings and seafoods, such as salmon and tuna, Kuhn says. Future work may focus on new equipment, such as microprocessor-controlled canning.

For now the center is focusing on canning, but may expand to study freezing, drying and pickling techniques. Andress, who with Kuhn organized a graduate-level seminar for extension personnel held at The Louisiana State University last year, says that each state issues pamphlets defining safe canning procedures, and “there is a lot of variety among them. A center can alleviate that problem.”

Dr. Sastry adds that the center can become a source of data for the industry and the consumer: “We should be influencing all recommendations being made by the U S. Department of Agriculture,” he says.

Kuhn says the equipment companies are looking to Penn State as a source of unbiased information. “Our name may not be on it, but it is likely that it began here,” he says of new advances in equipment for home canners.

The team recognizes that one of its hardest tasks may well be convincing people that what they learned at “grandmother’s knee” may not be the safest method to use. “We still have many doubters but we hope that will continue to change,” he said. [23] Altoona Mirror. Altoona, Pennsylvania. Wednesday, 27 Feburary 1985. Page D11.

By 1987, work was well underway:

With funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kuhn and his research technician, Tom Dimick, began a scientific study of home canning and freezing methods The USDA has designated Penn State a Center of Excellence in Food Preservation, the only such center in the nation. Kuhn serves as the center’s director. “ Our goal is to back up each food preservation recommendation with scientific research.” Kuhn said. “ We want to help people preserve higher quality food that has better color, cleaner flavor, longer shelf life and more nutrients than previous canning and freezing methods were capable of producing. “ We also want to re-educate people about safe preservation methods.” he added. “ Renewed interest in canning and freezing in 1975 resulted in a high incidence of botulism, which was traced to home canning methods.” [24]Penn State University offers free home canning and freezing guide. Greenville, Pennsylvania: Record-Argus. 23 September 1987. Page 5.

In 1988 the Penn State Center of Excellence published the first Complete Guide which brought together and superseded all the bulletins, pamphlets and booklets that had been published previously over the decades.

In 2000, the USDA established the National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP) in Georgia to act as the focus for its work on home food preservation, and to popularize, promote and advance its home canning work and advice:

The National Center for Home Food Preservation represents a decade of USDA-funded research carried out at the University of Georgia. The USDA has offered home canning and other home food preservation recommendations since the early 1900s. By the end of the century, it was time to review what was available. Extension agents on faculty at the University of Georgia applied for and received two grants that ran five years to cover the topic. “We were asked to do a literature review of a lot of the research that happened since the last major work at USDA, and determine some needs to do some more product development for their canning guides,” said Elizabeth Andress, professor and Extension Food Safety Specialist. “We developed probably 30-plus new canning recommendations, and we produced a video series. We produced the website, and the offerings on that include a free online course, and various outreach methods to help get out information from the USDA recommendations, also.” [25] Halloran, Amy. Preserving the Art of Canning Safely at Home. Seattle, Washington: Food Safety News. 26 April 2011. Accesssed March 2015.

The USDA has also continued to fund canning research at some university extensions, with all findings rolled up towards the center (in theory) of the NCHFP.

Research on food preservation is an on-going process. United States Department of Agriculture, and the Cooperative Extension Service continuously apply new research findings to their recommendations for food preservation techniques. The goals are to both increase food safety and improve food quality.” [26] Koukel, Sonja. Canning Fish in Jars. University of Alaska Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service. August 2010. Video. 00:43. Accessed March 2015.

No other country has invested in promoting safe home food preservation for consumers the way that America has, through the USDA.

History of USDA Canning Publications

Note that in general, new publications render previous ones outdated. The most recent USDA Complete Guide is the only one you should be using. The others are now of archival, historical interest only.

USDA Canning Publications (1909)

Farmer’s Bulletin 359

This Farmers’ Bulletin was the first USDA publication for home canning. It understood that heat was required for sterilization, and worked with two heat sterilization methods. The bulletin recommended sterilizing jars by “fractional sterilization”: boiling the jars for an hour a day for two or three successive days. The first day killed moulds and most bacteria, but left the spores. The second and third days would in theory kill the spores that germinated as the jars cooled down after the first boiling. The alternative second heat sterilization method was boiling jars for 5 hours straight

USDA Canning Publications (1917)

Farmers’ Bulletin 839, later named the “Home Canning by the One Period Cold Pack Method”

This bulletin focussed on how to operate canning equipment properly. It dropped the fractional sterilization method.

It worked with three heat sterilization methods: boiling water bath (100 C / 212 F), ‘water seal’ process (101 C / 214 F), and steam pressure processing at 5, 10 or 15 psi. For the jars, it recommended screw top containers.

Farmers’ Bulletin 853, named ‘Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables’

This complementary bulletin was issued a few months after Farmers’ Bulletin 839. It focused on the theory of sterilization and spoilage.

USDA Canning Publications (1921)

Farmers’ Bulletin 1211

This bulletin replaced 839 and 853. It covered processing and spoilage reasons.

A pause for change in approach and science (1920s to 1930s)

Until 1920, recommendations were based on what others experienced and reported, rather than on documented, tested scientific knowledge. Even in the commercial canning world, outbreaks of botulism from products were common. Knowledge of bacteria was still racing to catch up with the needs of the canning industry.

Before 1919, the USDA was operating under the assumption that botulism spores were killed by exposure to 80 C (175 F) heat for one hour, based on what textbooks at the time were saying. In 1919, however, the researcher Georgia Spooner Burke in her lab experiments found that the spores were surviving being boiled for 3.5 hours, and in 1921, H. Weiss found that spores were surviving being boiled for up to 5 hours.

In 1923, formulas were finally developed by Charles Ball which were reliable and became the basis for calculating thermal processing requirements for canning.

Between 1930 and 1935, research studies were done on meats, particularly chicken and beef. Subsequent publications included these results.

USDA Canning Publications (1936)

Farmer’s Bulletin 1762

This bulletin covered canning fruits, vegetables and meats. It gave processing times for jars and metal cans. For pressure canning, it recommended a pressure of 15 psi pressure (121 C / 250 F).

USDA Canning Publications (1942)

Conservation Bulletin 28, “Home Canning Fishery Products.”

This bulletin alerted people that under no circumstances should fish ever be canned by the boiling water bath method.

Agricultural War Information (AWI) publications (1943- 1945)

These publications were put out expressly to help the war effort. The goal was to dramatically increase home canned food in order to free up commercially-canned food for shipping out to feed troops and civilians in the war arenas.

1943 Wartime Canning Publications

- AWI 41 “Wartime Canning of Fruits and Vegetables” (replaced Farmers’ Bulletin 1762; encouraged people to share pressure canners owing to shortages of metal)

- AWI 61 “Canning Tomatoes”

- AWI 65 “Take care of pressure canners”

1944 Wartime Canning Publications

- AWI 93 “Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables” replaced both AWI 41 and AWI 61. In this publication, oven canning was pronounced dangerous because of explosions in the oven, and ineffective sterilization of the food, causing illness; open kettle canning was pronounced wasteful owing to all the resultant spoilage from ineffective sterilization.

- AWI 103 “Pickle and Relish Recipes”

1945 Wartime Canning Publications

- AWI 110 “Home Canning of Meat”, with assistance from the The National Canners Association (a commercial organization)

- Farmers Bulletin 1800 “Homemade jellies, jams, and preserves”

USDA Canning Publications (1946)

- Technical Bulletin No. 930 – “Home Canning Processes for Low Acid Foods.”

- Misc Publication 544 “Community Canning Centers”

USDA Canning Publications (1947)

- AIS 64 “Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables”

USDA Canning Publications (1952)

Picture Story 84 “Pork and beans… home canned”

This was the source of the much-loved home-canned brown beans / baked beans still in the USDA Complete Guide today, and adopted by Ball and Bernardin into their own canning guides.

USDA Canning Publications (1977)

- AIB Bulletin 410 “Growing, Freezing, Storing Garden Produce”

Recent times — USDA Complete Guides (1988 – onwards)

- 1988 USDA Complete Guide

- 1989 USDA Complete Guide

- 1994 USDA Complete Guide

- 2006 USDA Complete Guide

- 2009 USDA Complete Guide

- 2015 USDA Complete Guide

You can get a chapter by chapter PDF download version of it on the NCHFP site or a USDA Complete Canning Guide 2015. Merged PDF (merged Feb 2016) . HealthyCanning merged the above separate PDFs into one PDF for your convenience. You have our word that we made no alterations at all in the merge.

(The above list of publications may not be an exhaustive list; it is meant to bring forward some of the highlights. Source: Andress, Elizabeth L and Gerald Kuhn. Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. II. Early History of USDA Home Canning Recommendations. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, Cooperative Extension Service. 1983. Plus, additional research in archival libraries for other key publications. )

Related reading

National Center for Home Food Preservation

The USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning

USDA Recommendations for and against

Andress, Elizabeth L and Gerald Kuhn. Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. II. Early History of USDA Home Canning Recommendations. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, Cooperative Extension Service. 1983

References

Sharon frye

I am interested in the actual tests performed to determine canning times, densities, etc. I follow safe canning guidelines and understand the density concern. But if carrots have a density. of 16 g/metric tablespoon and rice has a density of 13 g/metric tablespoon….why can rice not be added to chicken soup? I’m a former physics teacher….and my curiosity is piqued. I an’t find any answers on line.

Healthy Canning

Hi Sharon, make a huge pot of tea or coffee, and on a nice rainy day or quiet evening, settle in and start reading all the backup here. There’s a wrath of it to be got through: https://nchfp.uga.edu/publications/usda/review/content.htm

Mike Harmon

This is another case of the USDA dictating to us how to eat and live that is just not acceptable from a group that is funded with our tax dollars.

We just ran into this problem with canning pumpkin puree or basically pumpkin pie fillings.

“Due to the large differences in the pumpkins sizes and area grown , we can not set a standard for their safe canning”

This is again unacceptable!

In the pumpkin’s problem there should have been a consistancy and ph standard that must be acheived [ by the consumer and the test facility] and then tests conducted.

I did not see the reasons for removing celery from the list.

Another reason given for pumpkin denial was that to ensure proper temperature in the canning jar would maybe cause the pumpkin to be over cooked and therefore not be acceptable to the consumer………… They should leave that to us to decide AFTER letting me know that . Yes, canning celery will not kill you IF===>etc

Many thanks for the post,

Mike

Healthy Canning

Hi Mike,

I did some digging on the celery canning recommendation for you. Turns out, it was actually Ball who gave and then withdrew the plain celery canning recommendations. You may wish to contact them to find out why. https://www.healthycanning.com/canning-celery/#history-of-home-canning-celery

As for the pumpkin purée I understand your frustration. You should consider writing to your elected representatives to tell them that this is a question that is important to you and other home canners, and that you’d like them to toss a few shekels to the NCFHP so that they could undertake research on this (after all, the government is never *not* going to spend your money, it might as well go on something useful, and they keep the NCHFP on bare life support.)

Anyway, I hope the Ball / celery information helps — at least you’ll know who to chase after! If you do manage to extract any information from them, let me know!