Home Preservation of fruit and Vegetables, 1989 edition. © Healthy Canning / 2021

Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables is a British home food preservation book. It was first published in 1926 by Oxford University Press with Margaret J. M. Watson as the author. [1]Review. “The Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables.” By Margaret J. M. Watson. 8vo. 142 pp. (University Press, Oxford, 1926.) 6s. net. Journal Of The Royal Horticultural Society. London: The Royal Horticultural Society. Vol-LII. 1927. Page 304.There were 14 editions in total, with 1989 being the last.

British home food preservationists often cite directions from this 1989 book as a British alternative countering other food preservation guidelines that they see as “American”.

For North Americans reading this review, note that the term “bottling” equals what they would call “canning”.

Note: this is not the same book as The Home Preservation of Fruit(s) and Vegetables by Lilian Peek (Texas College of Industrial Arts, 1918).

See also: Why the old British method of just “bottling” preserves is known to be unsafe now, Resources for Home Preserving in the United Kingdom

- 1 Summary

- 2 Dated knowledge

- 3 Processing methods

- 4 Jar closures

- 5 Fruit and tomato bottling

- 6 Freezing

- 7 Miscellaneous observations

- 8 Author of Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables

- 9 First edition of Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables 1926

- 10 Subsequent editions

- 11 1989 edition

- 12 1953 Crang and Sturdy Study

- 13 Other related historical publications

- 14 For further historical research

Summary

The book was first published in 1926 and has not been updated since 1989.

While it’s true that it was initially science and research-based, and very much ahead of its time in being so, much of that understanding of food science and safety from the 1920s is of course now very much out of date. Though several editions were issued, in terms of the recommendations being science-based the advances seem to have stopped by the 1950s (see Crang and Sturdy Study section further below), with further updates of the book not revisiting and questioning the underlying basis for the increasingly-dated science underlying those recommendations. The 1989 version does not even reflect food science from the 1980s, or 1970s for that matter, and so the recommendations in it are even further out of date than the 1989 date might imply. The underlying cause is that the UK government failed to make investments to keep the research current. In fact, in the 1980s, the Westminster government in London even abolished several food research institutes in cost-saving measures. [2]”1981 saw the disbandment of two of Long Ashton’s major research divisions, the Pomology and Plant Breeding Division and the Food and Beverage Division. This action by the ARC was a severe blow to the Research Station and began a long period of structural change. The Hirst Laboratory was built in 1983 as part of the reorganisation process, and work on arable crops substantially replaced Long Ashton’s long history of work on fruit and cider. The Agricultural and Food Research Council (AFRC, previously ARC) closed other research sites including the Letcombe Laboratory (1985) and the Weed Research Organisation (1986)” — Wikipedia, accessed June 2021 at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long_Ashton_Research_Station

In the United States, the pattern was identical up until the 1980s. At that point, the U.S. government realized there was an uptick in interest in home food preservation again, and with it, a corresponding uptick in food poisonings as flaws in the recommendations based on 1950s (and earlier) science revealed themselves. Consequently, the U.S. government reinvested in updating knowledge, questioned and retested every supposition, and in 1988 released the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Complete Guide to Home Canning, based on the new science and latest information. One year later, in 1989, the UK government released The Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables — based on all the old science and old information. The U.S. was publishing the future; the UK was publishing the past. The USDA Complete Guide has been continually revised since then, with the most recent update in 2015.

Aside from currency of information, there’s also a difference of approach between the U.S. and the U.K. food preservation guides.

The U.S. approach essentially aims for as close as it can get to 100% success rates in eliminating spoilage of preserved foods, and even more emphatically aims for 100% safety of the resultant products, with safety margins even deliberately built in. Perhaps not surprising, given how vocal Americans are about complaining over the slightest disappointment or suspected injury from a product. If anything, the U.S. approach has been criticized for tipping the scales to emphasize safety over quality, and for assuming that margins of safety are necessary because enough home food preservers will make mistakes or not follow directions.

The U.K. approach seems to be more “you will probably get good results, and will probably be okay safety wise” — often summed up with bravado by the phrase “just scrape the mould off”. There do not seem to be any safety margins built in the book’s directions, and it appears that the scales are tipped to quality: “The recommended processing times and temperatures are the lowest found to give adequate destruction of normal numbers of micro-organisms while producing the best flavour and appearance.” [3]Page 12. Notice the use of the word “adequate”, something you’d never see in the U.S. literature on the topic. And in terms of relying on “normal” loads of spoilage or pathogenic bacteria, U.S. researchers instead took the worst-case scenario into consideration.

Another difference is that the U.S. approach is more prescriptive — these are the methods and the equipment we support — and more geared to clear, defined rules: do this, don’t do that. The British approach is more descriptive and permissive: these are the various methods that people try, and these seem to be the results….

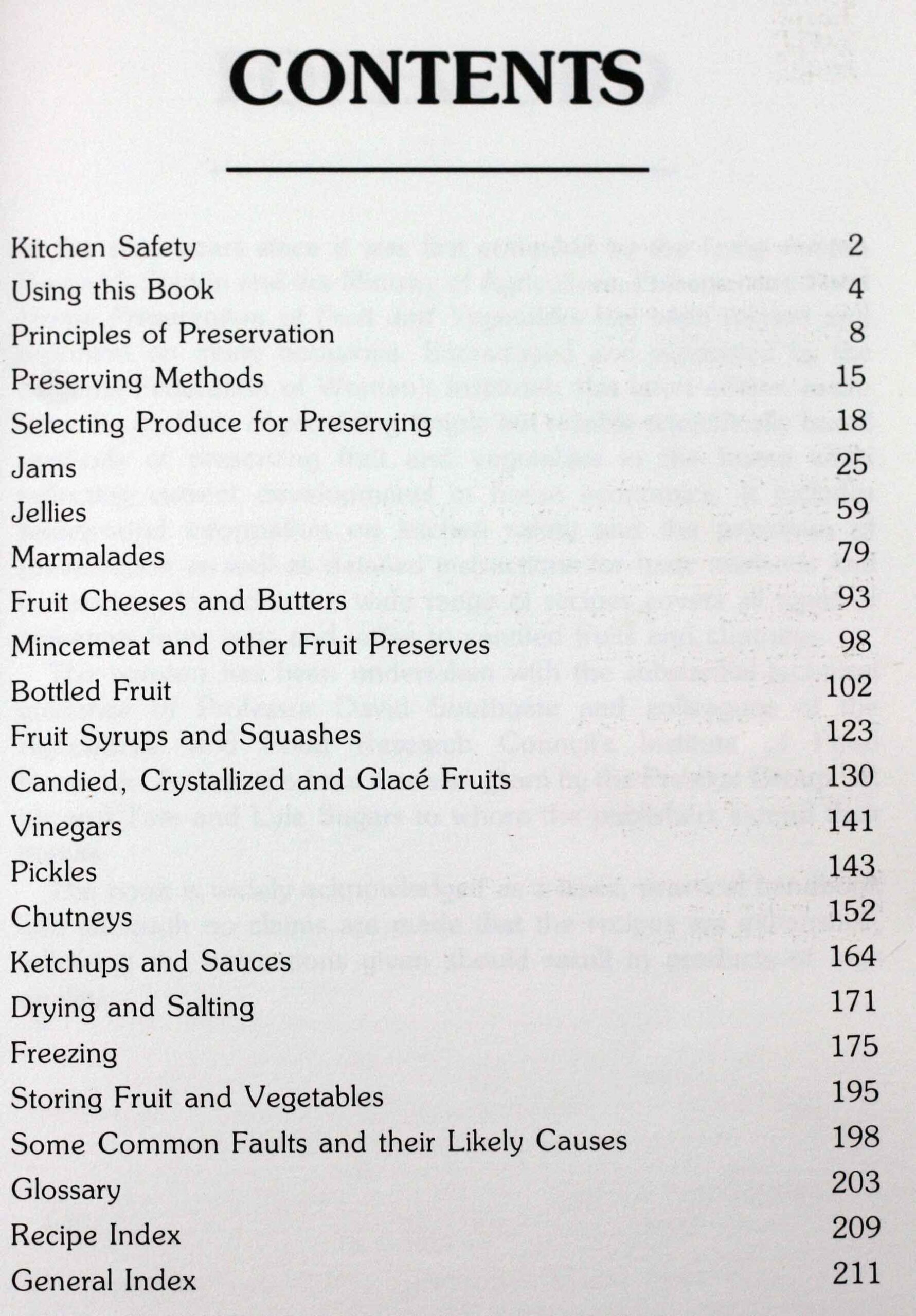

Sections of the book that still appear to be sound are those on Freezing, Candying Fruit, Drying and Salting, and, (Ambient) Storage of Hard fruits and Vegetables (e.g. in attics and root cellars).

The advice in the other sections is now problematic in terms of food safety and quality.

Home Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables, Table of Contents

Dated knowledge

This 1989 revision contains much information that is dated because the science and techniques have long since moved on.

One obvious piece of dated advice is to “Discard bottled preserves if they smell or taste peculiar” [4]Page 3.. The food safety advice now of course is, “If in doubt, throw it out” — and never to taste if there is the slightest reason to doubt. And for what it’s worth, it’s doubtful that even in 1989 food safety professionals would have been advising people to taste food they were dubious of, so that may have simply been dated advice carried forward from earlier editions.

Back in the 1980s, pectin products for low or no sugar jams were not widely available, so the book does not consider them and simply writes off low or no sugar preserves as “not true preserves”:

“It is possible to make jams with a lower sugar content but they can only be stored for a few weeks and open jars must be kept in the refrigerator. These are not true preserves because they do not keep well.” [5]Page 14

Compounding the problem is that the 1989 editor, Bridget Jones, doesn’t appear to have had either knowledge of, or resources to develop, processing times for any type of sealed jam jar, high or low sugar (or, it wasn’t her remit in editing the book.) We know now that processing times, as well as methods, are particularly critical for low-sugar preserves. The book says, “It is possible to make jams with less sugar than the amounts recommended but the preserve will not set as firmly and — more important — it will not keep well. Jams made with smaller quantities than those recommended can only be stored for a few weeks…. The jam should be potted in clean, hot jars immediately setting point is reached and covered at once with airtight lids. If the covers are suitable, the jars should be boiled in water for 5 minutes as for bottled fruit.” [6]Page 14

The 5 minute processing time comes across more as a Hail Mary measure.

Another piece of dated advice in the book was that the heyday of drying food to preserve it was over. “Drying has long been a widely used method of preserving food although it is no longer considered a practical method for preserving significant quantities of fruit or vegetables in the home.” Hindsight is 20-20, but ironically that statement was published just shortly before increasingly affordable consumer-grade dehydrators would start to flood the market, helping to create a revival in home food dehydration.

Processing methods

The section on processing methods (page 113) for food being preserved in jars is a mixed bag.

For starters, its opening principle is not a scientifically sound one. It states, “The processing method used depends on the equipment which you have at hand.” [7] Page 113/

Modern food safety experts would probably all agree that the processing method used must depend instead on the type of food being preserved, and that if you do not have the correct equipment to process that food in a certain way, then you find an alternative way to preserve it, such as freezing, or drying.

There are four “processing” methods for filled jars of preserves that the user can choose from, according to the book:

1. Slow Water Bath Method

This seems to be also called the “cold water bath method”.

This method starts with cold jars with cold contents going into cold water. The temperature of the water is raised to a certain point, being monitored by a thermometer in the water, and held there for a given period of time.

This method is similar to the to USDA “Low temperature pasteurization method” . One noticeable difference is that while this book gives this processing option for a wide range of food, the USDA only supports it for one or two specific recipes, with a caution not to use it for any recipe for which its use is not specifically indicated. A 1953 University of Bristol lab study found a great deal of spoilage with the ‘Slow Water Bath Method’ even after processing times up to 1 ½ hours. (See Crang and Sturdy Study section further below)

2. Quick Water Bath Method

This is the same as the standard boiling water canner method. Jars with heated contents in them go into heated water, are covered completely with water, and then boiled for a specified period of time.

3. Pressure Cookers

Pressure cookers that can operate at 5 lbs pressure are accepted in the book as alternative processing appliances for jars. Note: they accept any pressure device, and don’t require devices certified for preserving, as the USDA does.

4. Slow Oven Method

In this method, the filled jars are baked in an oven run at a lower temperature range.

The jars are filled with fruit, but no liquid. No lids are placed on the jars. The jars are baked in an oven, and then at the end of baking time, the jars are removed from the oven, topped up with boiling hot syrup, lids are put on, and the jars set aside to cool, being deemed fully “processed.”

5. Moderate Oven Method

In this method, the filled jars are baked in an oven run at a higher temperature range.

The jars are filled with fruit and boiling syrup. No lids are placed on the jars. The jars are baked in an oven, and then at the end of baking time, the jars are removed from the oven, lids are put on, and the jars are set aside to cool, being deemed fully “processed.”

Issues

Issues to focus on here are the pressure cooker and oven methods. Ordinary pressure cookers are now known to be wildly unreliable as canners in terms of both safety and results (see discussion here: Pressure Cookers vs Pressure Canners ).

Oven baking of jars as a bottling “processing” method has long since been repudiated by all home food preservation experts. It completely disregards that there are different types of glass tempering and that home food preservation jars are not tempered for dry heat, as, say, Pyrex is. Consequently, it is dangerous in terms of execution, with jars exploding in ovens. Even manufacturers of jars actively recommend against it, and will not accept the liability for people doing that. It’s also dangerous in terms of the result, which is uneven, unreliable sterilization of food owing to a variety of factors. See: Oven canning.

In 1953, a study by Alice Crang and Margaret Sturdy at the Agricultural and Horticultural Research Station in Long Ashton, Bristol was already pointing out all the problems with the oven “processing” methods, but despite this, the recommendations continued to be carried forward in this book:

“Slow oven processing of bottled fruit is not so reliable as the water-bath methods but often more convenient for the housewife. In the past, the processing time for this method was left largely to the experience of the preserver, who kept the jars in the oven ‘until the fruit looked cooked.’ It was found that the temperature of the fruit in the centre of the jar at this stage was far below the desired minimum but when the jar was filled with boiling syrup or water there was a rapid rise in temperature and, provided that the jars were not tightly packed, this might be sufficient to prevent spoilage…The cooling effect of the different loads in the oven is very marked in thermostatically controlled gas or electric ovens, and in some of the heat-storage cookers this problem is so serious that oven bottling cannot be recommended. The effect can be offset in the gas and electric and some solid-fuel ovens by varying the process time according to the quantity of fruit being processed; but such variations do not overcome the difficulty of uneven heating throughout the oven, so that the fruit in tall jars tends to be overcooked at the top before that at the bottom has reached a sufficiently high temperature. The method cannot be recommended when processing fruits with light-coloured flesh, as the warm, dry atmosphere encourages enzyme activity, and the fruit is spoilt in appearance and flavour before the boiling liquid is added at the end of the process.” [8]Crang, Alice and Margaret Sturdy. Bottled and canned fruit: studies of processing requirements and fuel consumptions by domestic methods. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 4 October 1953, Page 458.

Crang and Sturdy found the moderate oven method somewhat less problematic, owing to liquid being in the jar at the start of processing, but that also made it “difficult to allow the exact amount of headspace for the expansion of the liquid to ensure that at the end of processing the jars were full but had not overflowed…. ” They also found the method fuel inefficient: “This method is the most extravagant of those studied from the point of view of fuel consumption…” [9]Ibid.

And, as noted above, they found a great deal of shelf spoilage occurring with the ‘Slow Water Bath Method’ even after prolonged processing times.

For more information, see the section below: 1953 Crang and Sturdy Study.

Jar closures

In 1988, the USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning issued a clear recommendation against relying on any type of wax seal for preserves based on studies analysing results from the field over the previous several decades:

“Because of possible mold contamination, paraffin or wax seals are no longer recommended for any sweet spread, including jellies. To prevent growth of molds and loss of good flavor or color, fill products hot into sterile Mason jars, leaving ¼-inch headspace, seal with self-sealing lids, and process 5 minutes in a boiling-water canner. ” (1988 USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning. page 1 – 24)

Even though Bridget Jones was editing the book for publication in 1989, she persisted with supporting wax seals as a closure system for many types of preserves. (In fact, in terms of jar closure recommendations, little changed from the 1968 edition.)

Recommended closure systems are discussed on page 38:

“The keeping quality of home-made jam depends on the covering and storage. The type of covering used is very important. As soon as it is potted, the surface of jam should be topped with a waxed disc which perfectly fits the area without overlapping the edge of the jar. This should be smoothed out to exclude all air, sealing the surface of the jam and restricting the possible growth of mould.

There are two options for covering the pots: either cover the pots at once, as soon as you have potted the jam and put on the waxed discs, and while the jam is still very hot; alternatively, once the waxed discs are in place leave the jam until it is completely cold, then put the lids or covers on the pots. Do not cover the pots when the jam is warm, as moisture from the warm jam will collect inside the lid and without enough heat from the jam to kill the moulds, the preserve can turn mouldy.

Cellulose covers and elastic bands are commonly used to cover the pots. Lightly dampen one side of the cover and place the side uppermost over the pot, then pull it taut before securing the cover with an elastic band or string. The dampness allows the cover to be drawn tightly over the pot.

Twist-on lids can also be used to cover the pots but it is essential that these are sealed tightly in place as soon as the preserve is potted so that the contents remain sterile. The temperature of the jam must be over 77 C (170 F) and preferably over 82 C (180 F) when this type of lid is put on the pot. Screw-top jars which have a cardboard disc lining are not recommended as they tend to allow the growth of mould.” [10]Page 38.

Jars of jelly are recommended to be covered with wax discs:

“Cover the surface of the hot jelly with waxed paper, then cover the jars with cellophane covers while the jelly is very hot or when it has cooled completely… If the jelly is stored in a cupboard which is slightly damp or in a centrally heated store, then it is advisable to cover the surface of the waxed disc on the preserve with a thin layer of melted paraffin wax. The wax forms a tight steal when it is cold and set. Cover the tops of the pots with cellophane covers to keep them dust free.” [11]Page 66.

The book gives the following usage directions for wax discs with jam…

“Gently press a well-fitting wax disc on the surface of the jam, putting the waxed side down, and wipe the rim of each pot with a clean cloth, dipped in hot water and wrung out.” [12]Page 37.

and these directions for paraffin wax:

“The use of paraffin wax to seal the tops of pots is an old-fashioned idea that can still be very useful. The paraffin wax should be melted in an empty fruit can or similar, placed in a saucepan of hot water. When the wax has melted the can should be lifted carefully, using tongs or protecting your hands with a clean cloth. The preserve must be covered with a waxed disc first, then the wax can be poured on top, straight from the can. The whole of the surface of the preserve must be covered with the wax disc before paraffin wax is poured on top; this prevents the paraffin wax from coming in direct contact with the jam. Any leftover wax should be allowed to cool and harden before being stored in a covered container. When the was has set on top of the preserver a cellophane or clean cloth covered should be secured on top to keep off any dust and dirt. When the preserve is to be used, carefully run the point of a knife between the edge of the wax and the jar, then remove the wax in one piece. Lift off the wax disc and make sure that there is no wax left on the preserve. Discard the wax.” [13]Page 38.

The book does touch on two-piece lids, which would have been available then, but only gives directions for usage of the older-style which required some futzing: the directions don’t take into account the new Kilner two-piece self-sealing lids which had already been on the market for some time. These lids from Kilner (and other suppliers) which are now the standard come with directions which are adamant that no fiddling with the lids should happen: screw band on loosely and then after processing do not attempt to adjust seal because it will form naturally and interfering with this could prevent it happening.

Still, Bridget Jones when editing the book in 1989 left in these already-dated directions:

“Put the lid on the jar and fit the screw band or lip. It is essential that screw bands which are put on before processing are loosened by about a quarter turn, so that air and steam can escape when the jars are heated… Screw bands should be tightened immediately each jar is removed from the water bath.” [14] Pp 112 and 114.

These directions were for older style lids which had already largely disappeared from the market by then. In fact, this advice was just carried forward from older editions of the book.

Fruit and tomato bottling

The book’s fruit bottling section (pages 102 to 122) gives directions that go against most of the research-based, documented, and publicly available information that the USDA has released showing why certain factors go into required processing methods and times for bottling fruits. [15]Source: Andress, Elizabeth L and Gerald Kuhn. Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. II. Early History of USDA Home Canning Recommendations. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, Cooperative Extension Service. 1983

The preparation directions for preserving fruits in jars seems to start out generally sound. The book seems to realize that figs need acidification for safety — perhaps from USDA research on this that a researcher had learned about.

The book includes tomatoes in with fruits, and does give acidification directions for the tomatoes (as tomatoes cannot reliably be counted on to be below 4.6 in pH.) The directions call for ¼ teaspoon citric acid / 2 teaspoons lemon juice per 16 oz. / US pint jar. Again, the recommendations may have picked this up at some point from the U.S. research being disseminated, but the USDA lemon juice recommendation is actually 3 teaspoons.

However, the processing directions are all over the map and unnecessarily complicated, allowing for slow versus quick water baths, versus pressure cooking, versus slow versus moderate oven canning methods. (See Processing Methods above.) The book surmises (optimistically perhaps) that modern ovens generally have even heat distribution to be used for “processing”, but acknowledges that tall jars may be unevenly heated, that fruit tends to discolour, and that fruit which is tightly packed in jars may not do well with the slow oven canning method.

All water bath processing times are woefully inadequate. For 32 oz. (US quart) jar sizes, it calls for 2 minutes processing time for a jar of apple slices (the USDA’s time is 20 minutes), the same for a jar of rhubarb (the USDA time is 15 minutes), and 50 minutes for a similar size jar of whole raw tomatoes (the USDA’s time is 85 minutes).

On page 109, the book indicates figs require added acid (½ teaspoon citric acid per imperial pint; the USDA only wants ¼ teaspoon).

On page 121, fruit pulp and puree has a water bath processing time of 5 minutes (the USDA time is 15 minutes); tomato puree and tomato juice have 10 minutes (the USDA time is 40 minutes.) All are woefully inadequate processing times when compared to modern lab-tested processing time requirements. (See: Canning Tomatoes.)

The book does mention at one point that “The recommended processing times and temperatures are the lowest found to give adequate destruction of normal numbers of micro-organisms…” [16]Page 12. It could be that the writers of the book operated under looser definitions of “adequate” and “normal”, and that, unlike current practice, they built no safety-margins in, either.

To be clear, there’s nothing magic about U.S. researchers in this field. What they had in the 1980s was the advantage of later scientific knowledge to draw on, and just as importantly, government funding after the 1980s to keep on updating the research for home food preservation, which funding appears to have gone missing in the U.K. (the funding for home food preservation advancements also disappeared in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, so the U.K. was not alone in this.)

Freezing

In general, the freezing information in this book is sound, even with the passage of time (over 30 years at the time of this review), and mostly jives with advice from modern home economists on freezing techniques; even recommended blanching times for produce are close to those of the U.S.. Sugar syrup formulations are also close, though advice on whether to use light or heavy syrups with what specific fruits varies somewhat.

The understanding of the role of enzymes in degrading frozen food quality is correct: “Before certain foods are frozen they are blanched in boiling water to prevent the enzymes from adversely affecting the food…” [17]Page 182. However, the understanding of when the enzymal damage can occur is incorrect.

The book states that it can occur “during the time it takes to freeze and thaw before use.” In fact, damage from enzymes that have not been inactivated can also occur during the frozen period itself. When frozen, the enzymes are merely slowed down, not stopped altogether:

“If vegetables are not heated sufficiently, the enzymes will continue to be active during frozen storage.” [18]Barbosa-Cánovas, Gustavo V., Bilge Altunakar, and Danilo J. Mejía-Lorio. Freezing of fruits and Vegetables. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. 2005. Chapter 1, section 1.3.2.

And:

“There are enzymes (chemicals) in vegetables (and fruit) whose activity slows down but does not stop during freezing.” [19]McDonald, Sharon, Pennsylvania State University Senior Extension Educator/Food Safety Specialist. Four Frequently Asked Home Food Preservation Questions. The Daily American. 12 July 2021. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.dailyamerican.com/story/lifestyle/2021/07/12/four-frequently-asked-home-food-preservation-questions/7902239002/

Miscellaneous observations

The book advises that any preserves that develop mould should be discarded: “Discard bottled preserves if there is a mould on the surface”. [20]Page 3 and “Food which has turned mouldy should be discarded.” [21]Page 12 It’s not clear if this advice, coming in introductory notes to the book, was ever noticed, as some boosters of this book seem to be still of the “scrape and eat” camp, believing that “a little bit of penicillin won’t hurt ya'”.

The book doesn’t seem certain what a North American measuring spoon is. Which is fine: being British, there’s no requirement for the writers of the book to know this. But, the book comments on the issue regardless, and says: “American measuring spoons are very different [from British measuring spoons] and should not be used.” [22]Page 5. Then, in the table immediately following, it lists an English teaspoon as being 5 ml, and a tablespoon as being 15 ml — which is exactly the definition of North American measuring spoons for teaspoons and tablespoons. (See discussion of Measuring Spoons on CooksInfo.)

At the start of the book, it covers enzymes, and micro-organisms such as bacteria, yeasts, and moulds. [23]Pp 8 to 12 It shows awareness of the role they play in food spoilage, and is aware of Clostridium botulinum and the temperature needed to kill it (115 C / 240 F).

The book relies heavily on salt, sugar and acidity in its actual recipes to control spoilage organisms, but does indicate awareness of the role that heat processing of filled jars can also play.

“High concentrations of salt or sugar, and acid conditions found in pickles, inhibit the growth of bacteria. In acid conditions the majority of bacteria, including the spore-forming organisms, are unable to grow and they are more easily destroyed by heat when they are in this state.” [24]Page 10.

Heat processing does get mentions throughout the book (for instance, on page 12), but still, the book only draws on heat processing for maybe one-quarter of its recipes. For its jams and jellies, it relies solely on high concentrations of sugar to keep them, rather than any heat processing:

“Most micro-organisms will not develop in sugar solutions of 40 – 50 per cent, but certain yeasts and moulds are able to develop in these, and higher, concentrations. A minimum of 60 per cent added sugar, by weight, is essential in jam, jellies and marmalades.” [25]Page 14

In contrast, in the United States, by 1978 the official recommendation was to water bath heat process all jellies, jams, conserves, and marmalades. [26]Andress, Elizabeth L and Gerald Kuhn. Critical Review of Home Preservation Literature and Current Research. Athens, GA: University of Georgia, Cooperative Extension Service. 1983.

The book is aware of the role acidity can play in home food preservation, but is concerned primarily about its role in quality, not in safety. For instance, the book says: “Acid is not only important for setting the jam, it also brightens the colour of the preserve, it may improve the flavour and it helps to prevent crystallization of the sugar.” [27]Page 29. There’s no mention of the health issues that could occur if a jam with a pH above 4.6 is attempted, for instance. When it comes to pickles, it does mention the role of acids in controlling micro organisms: “Acids in preserving: Most micro-organisms do not grow well in acid conditions and this factor is important in the preparation of pickles… it is important that the strength of the vinegar is not diluted.” [28]Page 14

As far as the choice of sugar in jam goes, the book notes that while any refined cane or beet sugar can be used for jam, larger-crystal preserving sugar or lump sugar will produce less scum in the pot while boiling jams. It also gives this tip about removing that scum: “Do not remove scum from jam during cooking; do this when the preserve has finished boiling. Continuous skimming is unnecessary and wasteful.” [29]Page 43

Compared to USDA shelf life guarantees of at least a year, the guarantees for shelf life given in this book are very iffy and conditional. This could be because wax seals on jars offer less protection from the environment. It notes:

“The jam should be stored in a cool, dark place to retain its colour. The store must be ventilated, dry and free from many vermin. If the jam is stored in damp, poorly ventilated conditions it may ferment or become mouldy. In very dry conditions the jam may shrink badly and if it is to be stored in a centrally heated area, then lids which form an airtight seal should be used. Most jams which have [been] prepared, cooked and potted correctly, also jellies and marmalades, will keep under the right conditions for 6 to 12 months.” [30]Page 39

The book also notes that jam which is under-boiled in the jam pot, or which contains too little sugar, will ferment on keeping. This is not surprising, given that the jars of jam are not heat processed to kill any air mould spores which entered the jars along with the jam, and that many of the jars may end up with an imperfect closure system such as wax being applied to them. [31]Page 43

The jam recipes are to be found on pages 44 to 58. No pectin is used, instead the recipes rely on a traditional long boil with lots of sugar and sufficient acid to achieve a pectin set. All omit any heat processing step for the filled jars.

The jelly recipes fall on pages 59 to 78. None of the recipes call for heat processing of the filled jars. No pectin is used, rather the recipes rely on a traditional long boil with lots of sugar and sufficient acid to achieve a pectin set. The book adds a practical note about the types of fruit that were traditionally used in England for jellies: “The yield when making jelly is smaller than that for jam, so the cheaper fruits and those which grow in the wild are often used for economy.”

The marmalade section is on pages 79 to 92. In addition to standard preparation methods for preparing the mixture, the book also handily covers how to freeze fruit and then use it later for marmalade, and, how to use a pressure cooker to speed up the preparation process. Again, though, heat processing directions for the filled jars are sadly absent. A general jar closure direction is given for all marmalade recipes provided: “Waxed circles should be smoothed on the surface of the hot marmalade [in the jars] but the pots [Ed: jars] are covered when cold.” [32]Page 84

The fruit butters and fruit cheeses section starts on page 93. The problems with the book’s jar heat treatments — or lack thereof — become apparent when a bit less sugar is used in its recipes– and it does admit this. For example, with fruit butters. “[Fruit] butters have a fairly low concentration of sugar and they do not keep as well as jams and other preserves. They will keep to 2 – 3 months unopened.” [33]page 93 Compare this with the 1988 USDA Guide, which has you process the jars of fruit butters (5 minutes for pints, 10 minutes for quarts), and promises you a shelf life of at least a year. [34]USDA Complete Guide, 2015. Page 2-2. The book does, however, advise later on in the section: “For long keeping the pots should be processed as for bottled fruit purée.” [35]page 94.

The prepared mixtures for fruit cheeses are to be poured into warm jars, whose insides have been coated with a small amount of glycerin. The surface is to be covered with melted wax or a waxed disc of paper. Then the jar should be covered and stored. Again, no heat treatment for longer, higher quality preservation.

Pages 98 and 99 give directions for making a rumtopf.

The book’s directions for products with animal products in them — lemon curd with eggs (page 100) and mincemeat with suet fat (page 101) — completely omit any recommendation to process and vacuum seal the jars, but rather simply have you cover the jars with wax discs instead.

Pages 123 to 129 cover making and bottling fruit juices and syrups. Bottling directions include processing in a boiling water bath, and recommended closure systems for the juice bottles include corks covered in wax.

The section on Candied, Crystallized and Glacé Fruits (pages 130 to 140) appears to still be sound:

“All three types of preserved fruits are based on the same basic method of preparation and the difference is in the finish. Candied fruits are dry and they are often given a crystalized or glacé finish. A crystallized finish is achieved by rolling the fruit in sugar and a glacé finish is produced by coating the preserved fruit in a fresh syrup which is then carefully dried…… The fruit is covered with a diluted hot syrup, which is gradually increased in sugar content on a daily basis until it becomes a heavy syrup. In this way, the fruit is slowly impregnated with sugar which acts as a preservative. It is recommended that glucose or dextrose is used in place of part of the sugar, particularly when prepared candied peel. If liquid glucose is used the weight should be increased by one-fifth…. It is essential that the process of slowly increasing the concentration of sugar in the syrup is followed as this allows the water which is present in the fruit to diffuse out slowly as the sugar penetrates it. Unless the process is gradual the fruit will become shrivelled in appearance and tough in texture.” [36] Page 130.

Author of Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables

The original author of “Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables” was Margaret J.M. Watson of Scotland.

Watson was a “diplomée” from the Edinburgh School of Cookery and Domestic Science, and had a Certificate in Applied Science from King’s College for Women.

In 1925, Watson was made the Inspectress of Domestic Subjects, Northern Division (Moray, Nairn, and Banff) for the Scottish Education Department, with headquarters in Aberdeen. [37]Nairnshire Telegraph and General Advertiser for the Northern Counties. Tuesday, 13 October 1925. Page 4, col. 7. [38]Aberdeen, Scotland: Aberdeen Press and Journal. Tuesday, 6 October 1925. Page 5, col. 5, bottom. Later, she held a position at the Fruit and Vegetable Preservation Research Station Research (founded 1919) in Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire, part of Bristol University, as chief demonstrator of home food preservation. [39]Foreword to 1926 edition.

We don’t have any additional biographical information about Watson.

Much of the early work in England on home food preservation was out of the University of Bristol at this research station, which was a centre of study for information for the burgeoning commercial canning industry. The Institute and its original buildings are still extant; it is now (2021) named the Campden BRI and focusses on innovation and safety for the food and drink industry.

Another important research institute attached to the University of Bristol was at Long Ashton.

First edition of Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables 1926

The first edition was published in 1926. [40]New Library Books. Rochdale, Manchester: Rochdale Observer. 9 December 1939. Page 8, col. 5.

It even got reviewed in the New York Times in March 1927, and received a favourable nod:

“Although this is an English book, American housewives of the modern, progressive kind will find it useful because of its scientific character, for most of the American works on this subject prepared for their use deal only or chiefly with empiric methods, and their recipes and directions are the result solely of practical experience. Miss Watson is an English woman who has had years of scientific training in cookery and domestic science, and her special preparation for the writing of this book is indicated by the fact that she held for some time the position of demonstrator in food preservation in the Campden Research Station of Bristol University.

Most of her book is devoted to exposition of the scientific principles upon which success in the preservation of fruits and vegetables by the various methods which she describes. But in each case there are many practical recipes with detailed instruction for selecting the fruits best fitted for that method, preparing them and applying the principles which have been explained. The American reader will be surprised to learn from Miss Watson’s pages how little attention apparently has been paid in English homes to the home preservation of fruits and vegetables. ” [41]New York Times. Brief Reviews. 13 March 1927. Page 10, 12.

However, in the category of prophets not being honoured in their own home towns, in the same year back in England the book got an indifferent review from someone at the Royal Horticultural Society, who criticizes it for being too scientific at some points:

“The Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables.” By Margaret J. M. Watson. 8vo. 142 pp. (University Press, Oxford, 1926.) 6s. net.

This handbook is addressed by the author to Students of Horticulture, Domestic Science Teachers, Lecturers to Women’s Institutes, and all those interested in the Conservation of Home-grown Fruit and Vegetables.

It covers a wide field; bottling and canning of fruit, bottling of vegetables, drying of fruit, vegetables and herbs, preparation of fruit jellies, fruit butters and cheeses, marmalades, fruit juices, syrup, and vinegar, crystallized and glacé fruits, brining, and pickling. Some of these subjects are treated at length, whereas others are dealt with very perfunctorily. An example of the latter is found under the section of fruit juices devoted to home-made wines, where the only information given is an 18th-century recipe. On the other hand, in the theory of jam-making, we find an excursion into bio-chemistry; much of this Chapter will not be very intelligible to the ordinary housewife, who, beside the excursion referred to above, has to work out a somewhat difficult vulgar fraction and has to weigh the jam at intervals during the boiling out in order to obtain the amount of sugar required in May Duke cherry jam when finished.

In these days, when a constant supply of vegetables can be maintained from an ordinary garden all the winter, and while fresh fruit in immense variety reaches these shores throughout the year, it is doubtful whether the home preservation of fruit and vegetables on a considerable scale is worth while in this country. At the same time some people like to preserve soft fruit and also, during a glut, plums, and to these this book, which appears to be based on a series of lectures to students, should be of use.

It is pleasant to find in a book which largely consists of recipes and quantities, and puts fruits into a modern contraption called a “sanitary tin,” the old expressions “hulling strawberries,” “strigging currants,” [42]Harvesting currants by picking the fruit clusters (strigs) rather than the individual berries. and “topping and tailing gooseberries,” while a human note is struck by a solitary table recipe, “How to serve preserved asparagus.” [43]Journal Of The Royal Horticultural Society. London: The Royal Horticultural Society. Vol-LII. 1927. Page 304.

At some point in subsequent editions, publication was taken over by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

Subsequent editions

In 1968, the 12th edition appeared [44]British Library catalogue entry gives 1968 date for 12th edition. System number 008899777 with an added section on freezing foods, acknowledging the growing availability and popularity of home freezers:

“A new section describing the methods of preparing, packing and processing of fruits and vegetables by deep freezing has been included in the 12th edition of Home Preservation of Fruits and Vegetables (HMSO, 9s 6 d.)” [45]London, England: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. Monday, 1 December 1969. Page 9, col. 4.

Reviewers said it contained “the latest recommended techniques”:

“Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables. The twelfth edition of this best-selling title has been brought up-to-date to include the latest recommended techniques, and there is a considerable amount of extra new material. This includes the methods of preparing, packing and processing fruits and vegetables by deep-freezing, which is described in some detail, together with information on the type of domestic freezer generally available and the points to be considered in their running and maintenance. Bulletin 21. 9s 6d (by post 10s 4 d).” [46]Kensington Post. Friday, 11 September 1970. Page 39, col. 5.

The 13th edition was issued in 1971. As this was post decimalisation of currency, the price become 47 ½ p:

“And since you’re obviously interested in the making of home preserves, you might like to know of an excellent book called “Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables” that is issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. It’s available from any Government Bookshop, and I’m sure you’d find it immensely helpful. Price 47 ½ p.” [47]Drake, Pat. When a bargain is not the best buy. Coventry, England: Coventry Evening Telegraph. Thursday, 24 August 1972. Page 67, col. 7.

1989 edition

The final edition published was that of 1989, which was the 14th edition, and is the edition in question being discussed here.

Jones, Bridget, Ed. Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables. HMSO Publications Centre. London. Buckle, K.A., R.A. Edward., G.H. Fleet, M. Wootton . 14th edition. 1989. 216 pages. ISBN: 0112428649, 9780112428640 [48]https://www.bookdepository.com/Home-Preservation-Fruit-Vegetables-Min-Fish-Food-Agriculture/9780112428640

The 1989 edition is a paperback book with 216 pages. It was edited by a home economist named Bridget Jones [49]In fact, revision and design credit for the book is given to a company called “Complete Editions”, with Jones listed as the editor, and a Jane Brewster as the illustrator. They may have farmed out work on the book to Jones to do through her company. for the “Institute of Food Research” (created in 1968) in Norwich, Norfolk, which at the time was under the umbrella of the Agricultural and Food Research Council (AFRC). The AFRC existed from 1983 to 1994, with the remit of funding developments in farming and horticulture. After having closed or sold off many research stations, the AFRC was replaced by the “Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council” in 1994. The Institute of Food Research survived the demise of the AFRC, becoming the “Quadram Institute Bioscience” in 2017 [50]Institute Of Food Research transitions into Quadram Institute Bioscience. Press release. 27 April 2017. Accessed June 2021 at https://quadram.ac.uk/institute-food-research-transitions-quadram-institute-bioscience/, but Healthy Canning is not aware of any further work being done by them on home food preservation since 1989. The Quadram Institute does not appear to have any goals at this time of writing that would [51]Research Areas. Quadrum Institute. Accessed June 2021 at https://quadram.ac.uk/our-science/research-areas/ include home food preservation.

Promotional material released by the publishing house (HMSO Publications) for the 1989 edition noted that as the previous edition had been in 1971, this new 1989 edition was necessary to keep up with changes that had happened in the intervening 18 years:

“This new edition takes account of the many social and technological changes that have occurred since it first appeared in 1971. The text has been written by a home economist and validated by the AFRC’s Research Institute in Norwich. Topics covered include bottling, salting, freezing and pickling.” [52]H.M. Stationery Office. Accessed June 2021 at https://books.google.ca/books/about/Home_Preservation_of_Fruit_and_Vegetable.html?id=j5FAPQAACAAJ&redir_esc=y (Note that the “first appeared in 1971” is of course erroneous.)

The book has been out of print since at least 2015, if not well and truly before. In 2015 a blogger mentioning it wrote: “After the 14th edition of this “bible” of preserving was published in 1989, it went out of print due to lack of demand, according to the publisher.” [53]Lloyd, Vivien. Favourite Preserving Books. Blog entry 5 September 2015. Accessed June 2021 at http://www.vivienlloyd.com/favourite-preserving-books/2891/

Bridget Jones would also later author a book titled “Cooking and Kitchen skills” in 1991 for the same Institute of Food Research.

As for whether there were any actual updated lab research done behind the 1989 edition recommendations, and if so by whom, where and when, or whether old recommendations were just carried forward without retesting in light of all the new food science and safety information that had been published in peer-reviewed journals in the 1970s and 1980s on both sides of the Atlantic — we have no idea. Though the book does mention that “numerous experiments have been carried out to determine safe processing times to ensure that the organisms are destroyed in the bottling of foods” [54]Page 11, it does not mention what era these took place in. Given that none of the processing and technique recommendations substantially changed from earlier editions, as they surely would have if current information had been drawn on, it does seem likely that the recommendations were based on the scientific and food safety assumptions from decades gone by, already dated at the time.

1953 Crang and Sturdy Study

In 1953, a science-based study was done of home bottling (canning) techniques by Alice Crang and Margaret Sturdy at the Agricultural and Horticultural Research Station in Long Ashton, Bristol, associated with the University of Bristol.

The paper they wrote was both descriptive and prescriptive. Much of it appears to have been reflected in editions of Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables — or perhaps it was the other way round. In any event, it reveals the understanding of the science behind home food preservation at the start of the 1950s. Similar studies with similar results were being done in the United States at the time, too.

Among other things, they found problems with oven canning (a passage from them was cited in the section above on processing methods), but, they still did not come out and clearly recommend against it.

It’s important to bear in mind that as thorough as their research was for the 1950s, their paper also shows that they were conscious of the need to be surveying the field for new developments and findings in the field, of which there have been many critical ones to emerge since that time. If they were doing their paper now, no doubt it would be completely changed in the light of present-day knowledge.

The study can be downloaded here: Crang, Alice and Margaret Sturdy. Bottled and canned fruit: studies of processing requirements and fuel consumptions by domestic methods. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 4 October 1953, Page 449 – 459.

A 1930 newspaper column mentions Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables, but also mentions additional sources of home food preservation information available at the time:

“Domestic Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables. It is in the interests of the growers and the public alike that the fullest possible uses should be made of homegrown fruit and vegetables, and to this end much larger quantities might be preserved in the seasons of plenty for use at other times of the year. Plums are in abundance and obtainable at a remarkably cheap rate. Mr J. Stoney, the county horticultural superintendent, who has specialised in fruit preservation, informs us that he is having numerous enquiries with reference to the pamphlet issued by the County Education Committee and given away at demonstrations and lectures on fruit preservation. The pamphlet is out of print, and has been superseded by the publication of ‘Domestic Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables’ issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, 10, Whitehall Place, London, S.W.1. price 1 /- post free. Mr Stoney considers that this publication covers a wide field, and gives full details of the principles of preservation, fruit-canning, fruit bottling, principles and practice of jam-making, preparation of jellies, fruit syrups, candied, crystalised fruits, and the preparation of chutneys and jellies. He says that certain members of the public are apt to neglect the purchase of these cheap publications, and he considers it important that every housewife interested in fruit and vegetable preserves should read the latest. Asked as to what he considered the best books to study on the subject, he remarked that he himself can still find interest in reading ‘Successful Canning and Preserving’ by Ola Powell, a practical handbook for schools, clubs and home use, but probably the best book for the housewife is ‘The Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables’ by Margaret J.M. Watson, published by the Oxford University Press. The latest publication issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, however, embodies all the chief points in both the above books along with particulars of research work and assistance in the publication has been given by Professor B.T.P. Barker and the staff of the Campden Research Station, in particular Mr F. Hirst, Mr W.B. Adam, and Miss M.L. Adams. Housewives of the present day are more anxious to know the why and wherefore of the subject, and they will find their difficulties solved in the Ministry’s publication referred to.” — Domestic preservation of fruit and vegetables. Staffordshire Advertiser. Stafford, Staffordshire. 6 September 1930. Page 3, col. 6.

Other publications included the “ABC” series, also put out by the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. The series covered several different aspects of cookery, finally joined by one called “The ABC of Preserving“. [55]Imperial War Museum. Souvenirs and Ephemera. Accessed June 2021 at https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1502004264 The first edition, due to appear in October 1949, was delayed:

“Jam Tomorrow. Notice to publishers: The production of the Stationery Office booklet, “The ABC of Preserving” has been unavoidably delayed.” [56]London, England: Daily Herald. Tuesday, 4 October 1949. Page 2, col. 8.

But it finally made its first appearance at the end of November that year. Remember, rationing was still ongoing in the U.K., so even though wartime was over, home food preservation would still have been a valuable skill.

Advertisement for ABC of Preserving (bottom right corner). London, England: Daily Mirror. Monday, 28 November 1949. Page 10, col. 2.

There were at least 5 editions of the ABC of Preserving: 1949, 1952, 1955, 1960, and 1969. The 1952 edition (dated 1 January 1952) was 33 pages. [57]Accessed June 2021 at https://www.amazon.co.uk/ABC-preserving-Ministry-Food/dp/B001A9K55A The 1960 edition (dated 1 January 1960) was 30 pages. [58]Accessed June 2021 at https://www.amazon.co.uk/Preserving-Ministry-Agriculture-Fisheries-Britain/dp/B001P4QFSG

There was also later a freezing book, the “ABC of Home Freezing“, issued in 1978:

“ABC OF HOME FREEZING. A Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food Bulletin has just been issued: “An ABC of Home Freezing”, a practical handbook for users of home freezers. It is right up to date and will enable any potential buyer of a freezer to know what he can expect to get out of having a freezer. This comprehensive book contains chapters on the principles of home freezing; the economics of freezing at home; the care and use of a freezer; the choice and use of packaging; the freezing of vegetables, fruit, meats, poultry, fish, dairy produce and fats, eggs, ice cream and other ices. While there are numerous other books about home freezing food, this publication makes a valuable contribution in that all the recommendations and advice in it have been thoroughly tested by experimentation. This authoritative text is the result of over fifteen years’ work at the Ministry’s own Home Food Science Unit at Long Ashton Research Station near Bristol. All the chapters about particular foods have been checked for scientific accuracy by the staff of the Home Food Science Group, their specialist Ministry colleagues and the staff of the food research Institutes. Copies of the Bulletin are available from HM Stationer Office, or through book-sellers.” — Cheshire Observer. Friday 19 May 1978. Page 34, col. 6.

Also in the “family” was The ABC of Cookery (which was actually published before the preserving book).

For further historical research

Adam, William Bennett. A History of the Campden Research Station 1919-1965. 2007. Chipping Campden History Society. 2007/064/DS.

Annual Reports of the Fruit & Vegetable Preservation Research Station, Campden

Unless otherwise specified, page references are to Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables, 1989 edition.

References

OldGreyBeard

Thankyou for providing the 1954 Crang & Sturdy paper. Interesting reading. Did you notice that it didn’t have microbiology results for process (b) Quick water bath which is the closest to the USDA boiling water canning method? I thought that generally the microbiology section in the paper was weak compared to the microbiology in the USDA history you linked to.

The paper investigated three things:

1. microbiological safety of each process

2. effect of each process on the oxidase enzyme

3. cost of each process

whilst seeking to maintain the quality of the produce.

How much did this paper affect the published guidance?

I went back and looked at the notes & photos I took when I went to look at the earlier versions of the HMSO guide in Nov 2019 at the British Library (BL). For some reason or other I put this to one side for months…

Firstly, the dates of the editions of the guide:

Edition

Date first published

Title prefix

1

October 1929

Domestic

2

September 1930

Domestic

3

May 1933

Domestic

4

July 1936

Domestic

5

July 1937

Domestic

6

December 1942

Domestic

7

October 1948

Domestic

8

August 1954

Domestic

9

January 1958

Domestic

10

1962

Domestic

11

1966

Domestic

12

1968

Domestic

13

1971

Home

14

1989

Home

Editions were also reprinted so copies are found with later dates but these are the earliest dates for each edition.

I compared the processing times in the 1937 edition with the 1953 paper, the 1954 8th edition and the 1989 14th edition.

Between 1937 & 1954 some times & temps stayed the same, some went up and some went down. The times & temps in editions published after the 1953 paper are the same as shown in the paper. The only change I can see is the addition of citric acid to tomatoes pre-processing. This is in the 14th edition but not the 12th. The other change between these two editions is a table giving different syrup strengths. I didn’t take photos of the relevant pages on the 13th edition. Something for my next trip to the BL.

BTW the jars used by Crang & Sturdy must have been Original or Improved Kilner ones or Forsters or Forsters Atlas. I have a lot of these and they have much thicker glass than modern preserving jars.

I also obtained a copy of the 4th and last edition of Preserves for all Occasions by Alice Crang published by Penguin in 1954. The first edition was published in 1944. The fourth edition was written when sugar was still rationed and it comments that citrus fruits for marmalade have reappeared making the chapter on marmalades essential. The biography on the backcover gives a bit more information about Alice Crang (Her full name was Beatrice Alice Crang):

“Alice Crang was born in London in 1908, and educated at Putney High School, Queen’s College, London and Bedford College, where she obtained her B.Sc. Degree. It was whilst working at Messrs J. Lyons Research Laboratories that she first became interested in preserving. In 1938 Miss Crang joined the Long Ashton Research Station and has since specialized in the domestic side of preserving. Is as keenly interested in the cultivation as in the preservation of produce.”

A woman taking a BSc degree in the 1920s was really groundbreaking. J Lyons was a massive food manufacturer and retailer and this would have been a good job. Margaret Thatcher worked at the same laboratories as a scientist in the late 1940s early 1950s.

Alice didn’t marry (she would probably have had to resign her job) and died in 1960 at The Homeopathic Hospital in Bristol aged only 51. I don’t know why she died so young. She left an astonishing £14,204.

Margaret Sturdy was BSc from King’s College, London University too but I’ve not been able to find out much more about her.

The Crang book is interesting since not being an official publication or academic paper you get to hear the author’s voice. It uses the same times and temps for bottling as the 1953 paper but it omits the slow water method. Interesting.

What is very clear from reading theses various publications is that the British ones put a great deal of emphasis on the cost of methods, both in terms of kit and fuel. The USDA book doesn’t factor this in. This is why the oven methods are provided and methods for using jam jars and making your own lids. You don’t need to buy a large pan, you don’t need those expensive preserving jars. Very much “cheap & cheerful”, make do and mend”. The quality of the final result is given almost as much weight as the safety.

Given the nature of the period (1950s) in the UK, which is known as a period of severe austerity unlike in the USA, it’s easy to understand the emphasis on cost. If you want to find out more an excellent book is “Austerity Britain 1945-51” by David Kynaston.

The HMSO book does contain two examples of boiling water canning: of fruit purees and of fruit syrups.

I think the 14th edition published in 1989, also not a great time for many economically, should have been more ruthlessly edited and could well have benefited from the USDA research but my guess is that that wasn’t part of the brief and they didn’t have the resources. The chances of a 15th edition are, I would say, minimal. There is no UK equivalent to the National Center for Home Food Processing and Preservation.

If you’re going to use the British methods, use the quick water bath one. Then it’s only a short step to the USDA method as you just have to boil rather than simmer the water and increase the times.

I’ve found the slow water bath method to be fiddly and time consuming. I had to plot the temp every 10 mins to ensure I was heating the water at the correct rate. So much easier just to boil it.

Why not just use the USDA guide? Well, all the measurements are different. A US Pint & Quart are smaller than an imperial Pint and Quart and modern jars are all metric anyway. You could just use 500ml and 1L. Then there’s the use of cups for measurement when in the UK we weigh solid ingredients and use measuring jugs for liquids measured by volume. This is a useful set of conversions:

http://allrecipes.co.uk/how-to/44/cooking-conversions.aspx

I think you can adapt the USDA procedures with little risk as they obviously have so much contingency built in to them.

Healthy Canning

Fascinating! An invaluable and articulate contribution to the body of knowledge! Thank you for the time and work you’ve put into your thinking.

OldGreyBeard

As you can tell I find the whole subject of home preservation of fruit & veg fascinating. Your website is very helpful especially with its descriptions of techniques from other countries. Are you planning a page on preserving techniques in France?

Healthy Canning

Yes. One on Italy is also in the works.

OldGreyBeard

Forgot to say that I saw your reply when I was bottling pears using the USDA method. Second batch. I bottled rhubarb earlier this year using the USDA method as well. It has to be adjusted to take account of different weights & measures and jar sizes but it’s all pretty straightforward.

Given the current cost of natural gas in the UK I can see the point of the research behind the HMSO book placing a great deal of emphasis on fuel economy. The early 1950s really were an austere time for many.

Healthy Canning

The approval of steam canning has been a major step forward in water and cooking fuel conservation. Funding for the research should have come years ago, but then as you noted elsewhere, at least the Americans are doing something, while other countries invest diddly-squat in the field. Canada aligns itself with the U.S. on home food preservation and just rides for free on its coattails, not offering to put its hand in its pocket.

OldGreyBeard

A tough but essentially fair assessment of this book I think. I am British and have used this book a lot and have done some research into its origins and development as well. I also have some US books including the Ball Complete Book of Home Preserving, Home Canning for Dummies and a pdf of the USDA Complete Guide to Home Canning from 2015. The fundamental reason for my interest is that I have an allotment (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allotment_(gardening) a plot in a community garden) so have a lot of produce to preserve and the freezer is not of infinite capacity. I was born in the 1950s and studied Food Science at University in the 1970s although I subsequently worked as a software engineer.

I have a copy of the 1968 edition, courtesy of AbeBooks, and I’ve seen nearly all the others at the British Library. They are all bound into one volume. The 1929 edition is missing and I haven’t found another copy anywhere. My copy of the 1989 edition is in fact a commercially produced photocopy so I don’t have the front cover in glorious colour..

Freezing was added in 1954 but only a few pages. Freezers didn’t become more commonplace until the 1970s and this section seems to have been expanded then. My Mum bought a freezer in the early 1970s and that was imported from Finland. I remember that we had to change the mains plug. It was still working in 2013 when we cleared my parents’ house.

The sections in the book were added to or removed over the years as technology developed e.g. the freezer section was added and later expanded but the section on chemical preservation using Campden tablets was removed.

I think that the origins of the book are in the rationing in WW1. This was introduced in 1917 due to food shortages caused by problems with imports. It turned out that whilst the Royal Navy ruled the waves the U Boats ruled under them. Before WW1 Britain imported the bulk of its food. This was also the case at the start of WW2 which caused similar problems. Rationing ran from 1940 to 1954. Britain imports a great deal of its food today, the proportion having increased markedly since the 1970s.

The Foreword to the 1968 edition says:

“Earlier editions of this Bulletin were prepared by Mr F Hirst, Mr W B Adam and Miss M L Adams, at that time members of the University of Bristol Department of Agriculture and Horticulture; subsequent revision was undertaken by Miss B A Crang, BSc and her assistants at Long Ashton Research Station and be her successor Miss M. Leach”

The 1989 edition was basically an editing, metricating and rewording some sections job. The section on chemical preservation was thankfully removed as was the recommendation to wash & reuse wax used to seal jam jars. The bulk of the detail is exactly the same text as the 1968 edition. The metrication is crude. I find it easier to use the imperial measurements. Cook books of the 1950s and 1960s assumed a great deal more basic knowledge than those of today and that is reflected in the text of this book. I do find it gives the most detail about methods and the principles behind them compared to modern British preserving books which often just use the same techniques.

One factor which is evident in your criticism and the text itself is the emphasis on economy. The reuse of jars, using cheap jar covers, use the least fuel, use of foraged ingredients etc etc. You are correct to say that a degree of safety has been sacrificed in the interests of economy. I don’t think this makes the methods dangerous per se but they are more likely to be compared to the belts & braces US approach. The US approach assumes things will go wrong whereas the British one assumes they will go OK, usually.

The slow waterbath method is basically pasteurisation and is the one I’ve used. It is tricky to do on a gas hob as it’s very difficult to get the temperature to rise evenly and not too fast even with a thermometer. The method including temperature and timings in the 1989 edition is exactly the same as in the 1930 edition which is the earliest I have seen. I agree that the charge that the 1989 edition includes no new research for fruit bottling is correct. Essentially it relies on research which was at least 50 years old on publication and is now over 90 years old. Have we really learned nothing about microbiology in that time?

The quick water bath method isn’t the same as the boiling water canner method as the former only requires heating to simmering i.e. 88 degrees C.

Why isn’t there an updated version of the UK book?

The Government funded research establishment that produced the book was commercialised and privatised in the 1980s along with many other such establishments. These now focus entirely on money earning work for commercial clients. Who would pay for the book to be updated? The Government wouldn’t. The current Government doesn’t regard food supply as being one its responsibilities and have stated that the current supply line crisis causing the many gaps on supermarket shelves is up to the market to solve.

The only solution is to rely on the USA, again, as in so many other things. This is rather annoying but what can you do? Risk food poisoning? Gain comfort by wrapping myself in the Union flag whilst vomiting? The UK hasn’t invested in the guidance but relied on 90+ year old research and lack of interest in the subject to keep people safe. The US has invested and the USDA has made their canning guide available to all for free (those lovely people) on the web and of course there are the US books available for mailorder. There is also the guidance from various local extension programmes available on youtube and websites. To ignore the US advances doesn’t make sense.